The Black Range series by Australian photographer Ian Lobb and…

The Photograph Considered number thirty seven – Glenn Guy

I started my life in photography, just after my 17th birthday, working full time in a busy camera store in my hometown, Hamilton in Western Victoria. After operating a wedding/portrait studio I worked as a newspaper photographer before moving to Melbourne in 1986 to study photography.

During my first five years in the big smoke I supported the cost of my studies and travels by working in camera stores before commencing what seems like eight very long years at Kodak’s Australasian headquarters in Coburg.

I conned my way into a shift work job in the manufacturing division, while continuing to study full time. After a few customer service positions I changed over to part time study once I secured the job I wanted working in the Pro Passport and Photo Information departments in what became the Kodak Information Centre.

Eventually I moved onto the role of Product Manager in the Professional Imaging Division with a few added responsibilities including running the Q- LAB E-6 process monitoring program throughout Australasia and South East Asia.

In addition to my own creative projects I’ve stayed involved in the industry by teaching photography, at short course and tertiary level, for almost 30 years.

These days I teach mostly private, one-to-one photography courses designed to help folks realize their own creative vision.

Bridge, Yarra River, Melbourne

This photo of the undercarriage of a bridge over Melbourne’s Yarra River was one of the first large format images I made. I was drawn to the luminous qualities within the scene, in particular how the light brought the concrete piles to life and helped extend the sense of three dimensional space within the image.

It was 1990 and I was studying photography under Les Walkling at Phillip Institute Of Technology in Bundoora. After more than 40 years in the photography industry I still consider Les to have been my most important mentor. I ended up studying under him for seven years culminating in a Masters of Photography at RMIT in Melbourne.

This was one of the very first images I made with a large format camera. Perhaps that’s why I can still remember sweating it out under the dark cloth while I messed around in search of a cohesive and harmonious composition.

Trying to navigate the various knobs that controlled the camera’s tilt and shit mechanisms while composing the image, upside down and back to front on the camera’s ground glass screen, seemed beyond me at the time.

The resulting image was a bit cockeyed and I remember having to position the print at an angle to make the scene appear straight behind the window matte.

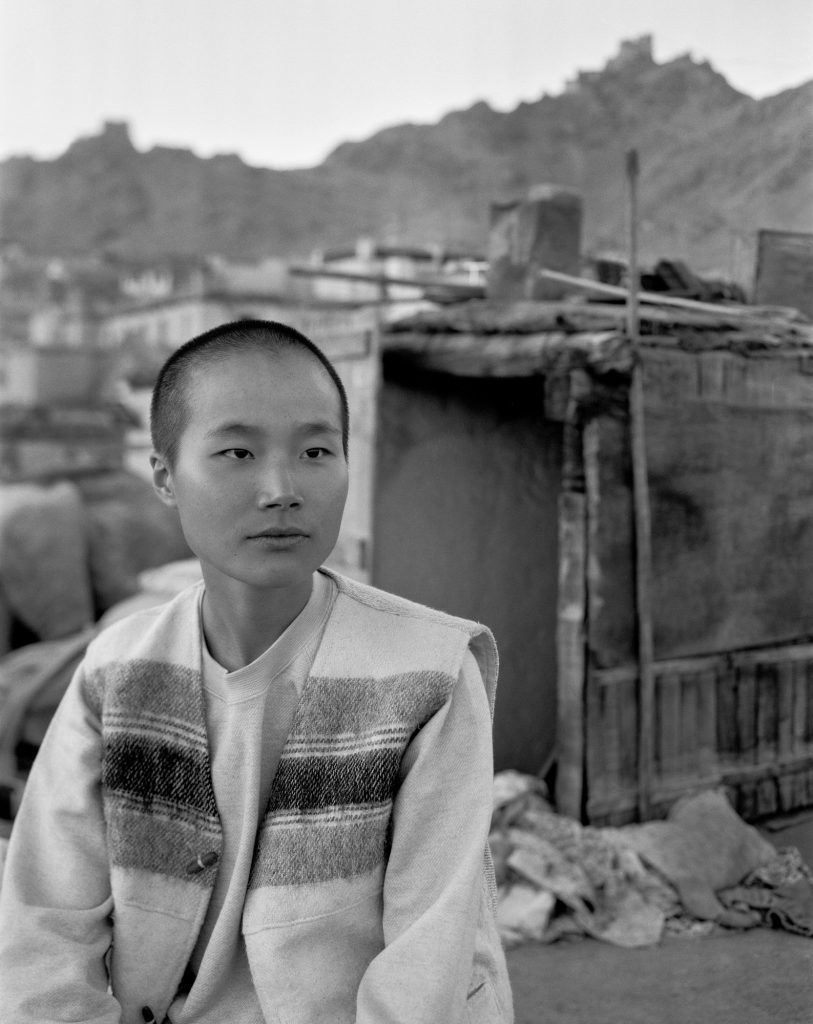

Buddhist Nun, Ladakh, India

Most of the projects I’ve undertaken since moving to Melbourne to study photography have been self motivated and self funded. These days I brand myself as a travel photographer. It allows me to marry my two great passions of travel and photography to explore my response to the people, landscapes and architectural sites I’ve visited.

I loved my 4 x 5 folding flatbed camera. I can’t remember the brand, but it was beautifully crafted in Japan comprising warm colored timber and shinny brass knobs.

But once you got past the bright and shinny aspect of the camera it wasn’t so great. The bellows leaked light like the proverbial sieve and the lens I’d purchased, second hand, was a disaster.

Despite having it repaired numerous times the inbuilt shutter kept sticking, jamming the apparatus and making the lens unusable.

I hadn’t had it long before I took my 4 x 5 kit on one of my trips over the Himalayas to Ladakh (Land Of The Passes) on the borders of India and Tibet. I remember taking a 100-sheet box of Kodak T-MAX 100 film, a few dark slides and a changing bag for the extended trip.

Unfortunately I only exposed about a dozen negatives before the lens jammed up. I was a poor student without a credit card and, after working all year to save for the trip, I just couldn’t afford to fund the purchase of a second lens.

I was staying in Leh and was advised to take the lens to the only repair place in town. From what I gathered the guy repaired old sewing machines. He accepted the lens and then promptly waved me away.

Later that day I popped back and was shocked to see him squirting Singer sewing machine oil at the lens. He hadn’t even taken it apart.

One of the few images I made on that trip features a South Korean nun who was on a holiday visiting Buddhist communities in Northern India. She was being chaperoned by a South Korean family and I had to convince them my motivation for photographing her was completely honorable.

We were staying at the same guesthouse, the Palace View Kidar, where I stayed during my first three visits to Ladakh. These were my early backpacking days and, out of my USD $10 a day budget, I seem to remember paying around USD $2 a night for accommodation.

It wasn’t fancy, but I formed a strong relationship with the family and staff who ran the place.

I loved the kids and quite fancied one of the workers: a girl from the nearby Nubra Valley, entry into which was banned to foreigners back then due to its close proximity to the border regions with Pakistan and China.

I remember almost expiring during an epic game of badminton with the kids father, a local champion. I did okay given the fact that I’d never played the game and experienced difficulty running around at altitude in the rarefied air.

Anyhoo, after convincing the nun’s minders that I wasn’t American (LOL) and that my intentions were pure I was permitted to make her photograph under close supervision.

We were having tea together in the family’s kitchen, where breakfast and dinner were served to guests. I asked about a staircase I’d noticed and was exciting to learn that it lead up to the rooftop.

That sounded exciting and, in the hope of creating a unique image, I asked for permission to take a look. I wasn’t disappointed. It was late afternoon and the light was gentle.

The young Buddhist nun was extremely humble, to the point of being shy. With no common language it was tricky to keep her still long enough for me to focus and make the image.

I remember working hard to construct a composition that provided sufficient tonal separation between the nun’s head and the background immediately surrounding her.

You might also notice how similar areas of tonality connect with each and lead the eye through the frame. It was a key consideration in achieving a relatively successful composition.

I love the subtle separation of tones within this image, particularly in the nun’s clothing. The subdued mood lends itself well to notions of nostalgia which I think is completely appropriate to the image.

I no longer have the darkroom print I produced from this negative, but it would have featured subtle tonal manipulation to enhance local contrast. In addition to dodging and burning I would have applied selective bleaching (i.e., Farmer’s Reducer) and Selenium toning to achieve the desired result.

I’ve only recently had the negative scanned by my great friend Matt from Matte Image in the inner Melbourne suburb of Richmond. Rather than forking out the big bucks for drum scans I opted for a flatbed scan of all three images featured in this post.

Back in the day Selenium toner was my preferred toner which I employed for local contrast enhancement and print longevity. In the case of this image the gentle orange stain from tea toning might have been beneficial to the highlights, particularly that near white sky.

Back then I used a Zone VI modified Pentax Spot Meter to determine exposure and calculate the dynamic range of the scene. After a while you develop an intuitive sense for contrast but, back then, taking separate light meter readings for important highlight and shadow areas was very much part of the learning experience.

While I added extra in-camera exposure in conjunction with N-1 and N-2 development, when photographing scenes of relatively high contrast with individual sheets of large format black and white film, I learned early on to avoid such high dynamic range scenes when working with medium format and 35mm roll film.

However, for some reason, I felt it would add a certain authenticity to the image if I allowed the sky to burn out on this occasion. It was about this time that I purchased a Samuel Bourne book and very bright skies where common in prints made from orthochromatic films used by 18th century photographers like Bourne.

Now that the original negative has been scanned I might be tempted to play around with a variety of heavier split toning options on the desktop.

However, for the sake of this article, I’ve tried to reproduce the image as close as possible to how I think it would have looked back in the day with the materials I used and the darkroom based skills I had at the time.

I hope you dig it.

Walkway and Grasses, Wilsons Promontory

The word documentary can be a bit tricky in so much as it can refer to both a genre of photography as well as the approach taken by the photographer to create their images.

Fundamental differences between a photograph as a document of so-called reality and a work of art reside, for the most part, in the intentions of the photographer.

One approach is primarily concerned with accurately recording the subject, scene or event depicted while the alternative is to approach the creation of the image in a way that points towards notions and realities beyond that which appear within the boundaries of the frame.

To take the discussion a step further it might be useful to define the primary differences between the notions of craft and art.

To that end we might think that craft concerns itself, primarily, with the technical aspects of making the image including camera, film and lens choice; composition; exposure, focus and depth of field; film and print processing; and display of the final image.

Art, on the other hand, concerns itself with the questions what, how and why. Of the three the most important, and the one that often determines the other two, is the question why.

Most of us are drawn intuitively to photograph certain things. Over time preferences are established and we construct our photography adventures around photographing the same sorts of things, again and again.

For most folks that involves photographing a particularly genre like portrait, landscape, architecture, wildlife or sport.

After a time you know what it is you like to photograph and, with experience, you begin to understand how to achieve good results, more often than not.

But have you ever thought about why it is you’re drawn to photograph the same sort of thing, again and again?

For those folks who make the distinction between subject and object the realization that what you photograph is not dependent upon any specific genre of photography is enlightening. You’re simply excited by what the scene offers in relation to light, composition, mood, message or theme and your ability to explore how you feel about what you see.

When it comes to portrait photography I’m influenced by a need to explore the human condition. However, all photos I create are underpinned by what I refer to as the transient, transforming and transcendental nature of light.

Composition was very much in my mind when constructing this photo of a boardwalk and grasses at Wilsons Promontory in South East Australia. Seeking the highest possible quality I employed my large format 4 x 5 camera, ISO 100 speed film and meticulous film and print processing to achieve the best results I was capable of at the time.

Such decisions speak to the craft involved in making this image. But any art inherent to this photograph is dependent upon the light that initially drew my attention and my ability to explore how I felt about what it was I saw at the time the camera’s shutter was tripped.

I decided to include this image as an example of what separates the notions of subject and object in photography. It’s not particularly sophisticated but, like the other pictures in this post, it demonstrates the beginning of my transition from object to subject based photography some 30 years ago.

While the boardwalk and grasses are the objects depicted the image is really an exploration of my response to the light, tone, line, shape and texture existing at that particular intersection of time and place.

Continuing the process in the darkroom, or on the desktop, allows us to pursue the journey of discovery and manifest something of what was glimpsed during the process of creating the original in-camera exposure.

Conclusion

While I have substantial experience in film and digital photography, including years of darkroom experience printing my own black and white and color prints, I never got beyond basic abilities with large format photography.

I doubt I kept my beautiful 4 x 5 flatbed camera for more than a semester and, due to having it serviced several times during that period, I may have only exposed a few dozens sheets of film in the time I had it.

Overtime I moved to Leica and Hasselblad film camera systems as I decided they delivered the combination of quality and relative ease of use I needed for the travel photography I was likely to undertake into the future.

Nonetheless, I understand the attraction of large format photography and I admire the passion folks who collect and actually continue to photograph in this medium have for their craft.

I’m really appreciative of the opportunity to connect with you in this space. This is a great site and I’ve known the editor, David Tatnall, for many years.

I’m a long time and passionate blogger and have operated the Travel Photography Guru website and blog since January 1, 2008. I still manage to publish 3 or more significant posts per week covering the art and craft of photography.

To date almost all images on that site have been produced with digital cameras. However, I’m about to begin copying hundreds, if not thousands, of 35 mm and medium format negatives and transparencies which will begin to feature in blog posts overtime.

I hope you’ll find your way over there some time soon. If you do, feel free to say hello via my site’s Contact page.

Glenn Guy, Travel Photography Guru

About Glenn Guy.

Next Post: Book: Winter Light by Grant Dixon

Previous Post: West Coast Granite Photography Workshop

Glenn, thank you for being part of The Photograph Considered series. Great article and photographs, I particularly like the nun on the roof, fantastic portrait. Congratulations.

It’s absolutely my pleasure David. You’ve created a beautiful and important site which I’II be sure to share with other folks who love fine art photography. Congratulations and keep up the great work.