Black Mountain Tree. Silver gelatin print. This is a photograph…

The Photograph Considered number thirty one – Iain Maclachlan

Stumbling upon William’s treasure. Salt print.

This image has taken a long time to emerge. It began with a challenge; how to express the void. I arrived at this point midway through a mentoring program I had commenced last year. Sitting amongst accomplished mid-career artists and professionals, it was a daunting task to step from amatuer to artist, and commence a body of work that felt personal, meaningful and worthy of expression. I felt devoid of ideas no matter how many diary entries I wrote.

I have always been interested in the mystery of liminal space as represented in photography of places. That strange midway inherent in the emotionally charged gothic landscape where the past coexists with the future, the familiar is not so familiar, objectivity questionable and the senses are haunted and challenged. With nothing but emptiness coming to mind, I bravely announced I would photograph the void – more out of exasperation that anything else.

With the aim of tackling nothingness rolling around in the back of my mind, I headed several times into my local bush in search of places that might evoke a sense of the uncanny in their tangled spaces. It didn’t take long before I found myself driving along a winding mountain road past a road sign that said ‘Welcome to Old Warburton’. The strange thing about this sign is that there is no township, just a bend in the road, and a further sign angrily calling on mountain bikers to stop. Something about Old Warbuton is important to the few local residents living on this mountain hillside. With little knowledge of its history, it seemed apt to explore by foot and venture upwards on a steep, heavily gutted and ravaged track, aptly named Mine Hill Track. Just evident running from the sides of the track were almost discernable paths, overgrown and damaged by time, barely a foot’s width wide. I began to traverse gingerly across the steep slopes questioning the sanity of what I was doing. Gradually I could see signs of diggings for gold underfoot; undulations in the terrain that at first seemed natural became the rounded hills and valleys formed from mullock heaps. At one time this mountain slope had been stripped bare for timber, water races constructed across the hill tops, and air heavy with the rhythmic sound of rock being crushed. A series of bushfires laid to ash all signs of human endeavour except the worked earth overgrown with scrub and mountain ash steadily reclaiming its own.

It was along one of these barely existing tracks that I stumbled on the open face of a mine just wide enough for a crouching man to enter. Dug by hand horizontally into the mountain, it stood in perfect silence, unaffected by time and appearing as if the miners were simply resting. It was unnerving and definitely felt as if I was trespassing but to whom was unclear. A well preserved fire pit sat on the only level ground immediately in front of mine entrance giving more weight to my sense of being watched. It was as if tools had momentarily been rested and the miners would soon return to their hidden workplace.

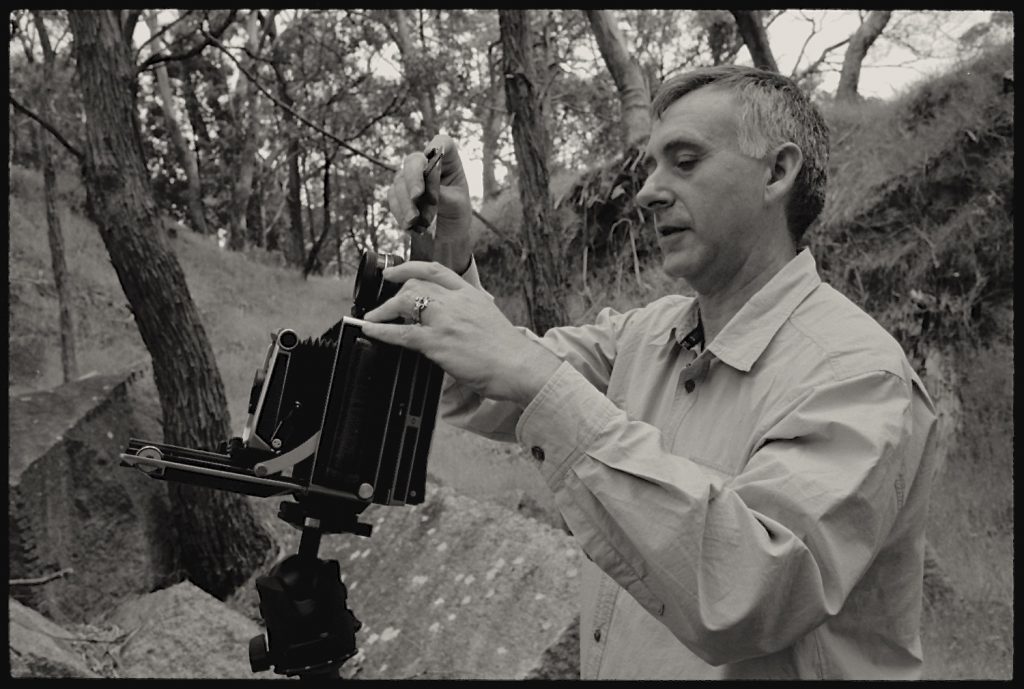

The image titled ‘Stumbling upon William’s treasure’ was made using a 4×5 Linhof Master Technika field camera. I prefer the depth of field control that large format brings and this type of image could not have been made with much else. There was only room on the narrow track for the tripod legs and so composing was done with an external viewfinder, and fine focusing achieved by leaning around from the side of the camera and applying a loupe onto the ground glass to check foreground and background focus. A little back tilt helped bring the fire pit into focus and also increased its prominence in the foreground. I had found a void! The lens used was a 125mm f5.6 Fujinon W, which I find a very useful focal length lens giving less distortion than a 90mm, and being very small and light with a good image circle sufficient for movements on a 4×5. For black and white landscapes I have standardised on Fomapan 100 exposed at EI 80 and developed in Beutler, or if shooting in mid summer, divided D23. This gives me a balance of sharp acutance and good tonal range with less risk of blown out highlights. The Fomapan films have a beautiful grain structure and are relatively thick emulsion films, so I find they are very responsive to different development techniques.

With printing the image, I had always imagined that it should be reasonably large at around 20 by 25 inches and be made by hand layering, allowing for chance and time to embed itself into the process. Wrestling with the void is messy, mysterious, emotive and iterative. A very experienced friend of mine, renowned for her camerless prints, suggested salt printing could yield the depth of details in the shadows I was looking for. So began a complex set of around 20 steps to make this first small test image measuring 17cm by 13.5cm. An alternative process print can take days and I like the way the image guides and informs each step as it evolves.

The initial base image comprises salted gelatin with two coats of silver nitrate brushed onto pre-shrunk Fabriano Artistico 310 gsm watercolour paper. A digital negative was made from the scanned film negative and printed onto Pictorico overhead transparency, then layed on the surface of the coated paper under a 3mm glass plate and exposed for 12 minutes under a 400 watt Metal Halide overhead factory light. Sunglasses necessary! The overhead light is approximately 20 cm from the paper surface and gives a good sharp image.

After developing in salt and citric acid, a gold borax solution was used to give more permanence to the print, which moved the image slightly towards plum colour but kept the depth of burnt umber colouring overall. At this stage the image had the benefit of fine details and long tonal range typical of a salt print but lacked the depth of emotion and darkness in the shadows that I was after. If gum was good enough for Edward Steichen to apply over platinum prints then perhaps I could use it too, but being a salt print, a strong protective barrier is needed before applying dichromate less the salt print disappears. I applied two coats of hardened gelatin sizing and then the first of three layers of gum, tinted with various strengths of ultramarine watercolour pigment at different exposure times, to split tone with more depth of blue in the shadows. Some research of painting techniques revealed that an ultramarine wash over burnt umber is a well-known technique dating back to the middle ages that forms a natural looking red-black; slippery and silvery depending on how the image is viewed relative to a light source due to its optical mixing of the layered colours. Development of the gum layers is ‘automatic’ by laying the print motionless in water, with some light brushing by hand to lift the highlight details in the centre of the image.

In late 2018 I commenced a mentorship programme with Paul Macdonald of Contact Sheet, Sydney, and challenged by Paul and fellow mentor Stephanie Rose Wood, I began to explore the elements of my existing photographic practice and sought to make some sense of the uncanny or fear expressed unconsciously within my work. This image forms a series that explores the Australian landscape, particularly of places haunted by past events or lost to present memory in the march of economic progress, that invites an emotional response to the Australian gothic myth. Without making these personal connections, it is my view we will continue to value this country in only selfish economic terms, fit for plunder and ongoing exploitation, rather than be inspired by its age, resilience and foreboding indifference.

In the modern era, we have lost connection with the spirit of our country. To live closely with the land is to feel its awe. With bushfires and pandemics once again sweeping the land, and the prospect of more climate terror yet to come, we are reminded of our smallness and dependence. As early as 1896, Marcus Clarke coined the term, ‘A weird melancholy’ to encapsulate the white-man’s experience of the Australian bush. He wrote,

Australia has rightly been named the Land of the Dawning. Wrapped in the midst of early morning her history looms vague and gigantic. The lonely horseman, riding between the moonlight and the day, sees vast shadows creeping across the shelterless and silent plains, hears strange noises in the primeval forests, where flourishes a vegetation long dead in other lands, and feels, despite his fortune, that the trim utilitarian civilisation which bred him shrinks into insignificance.

Returning to Old Warburton, what do we know of its history and fate? A fascinating aspect of this place is that it does not exist in any real sense. A township that barely lived, it was considered a ghost town by 1880. Early miners walked the tributaries of the upper Yarra river, seeking alluvial gold in the red tannin coloured dark wooded streams. Before long, they began moving higher onto the steeply sloped ravines following seeking the old riverbeds and quartz reefs. Along a stream named after him, James McAvoy, known to the other diggers as Yankee Jim, found gold and established a small mining camp in 1863. He had travelled to Australia via California after venturing out for adventure as a young man from his home of Nova Scotia as a teenager. Cannily, he initially hid his gold in buried glass jars lest others discover his success. By 1880, mining had reached industrial scale with the establishment of the Yarra Yarra Hydraulic Gold Sluicing Company. The company constructed eight kilometres of water races extended from Big Pat’s Creek and delivered 2,300 litres of water per minute down the side of Mount Tugwell scouring off the side of the mountain leaving a thirty metre cliff face. Complaints of the environmental damage caused by debris washing into the Yarra river, silting its mouth and spoiling farmland, soon started. By 1884 gold mining was all finished. The few remaining wooden buildings burnt down in 1929, and what remained, was further burnt in the Black Friday fires. A lost cemetery, with no gravestones or markings, is somewhere nearby. The township moved off the slopes and deep ravines to the present location of Warburton before the twentieth century had started.

My little mine lacks the industrial scale of the Yarra Yarra Gold Sluicing Company. Dug almost horizontally into the hill, the line of quartz seam being chased is clearly visible in the walls of the tunnel. In 1929 there was a brief second gold rush led by discovery of reef gold by an old miner William McCormick. As reported at the time, he had spent many years searching for reef gold amongst these foothills of heaped rock. Now forgotten by history, his hopes, excitement and ultimate disappointment remain forged in the land. I suspect this was his mine and he still keeps a keen interest in any visitors who stumble this quiet way. We might wonder what motivates a man to spend his life searching for a fleck of metal, but we can also look at ourselves and wonder what legacy we might leave behind in our efforts to create a life of meaning. For a moment at least, he held the infinite in his hands.

Iain Maclachlan is a self-taught Melbourne analogue photographer and lecturer in postgraduate economics and finance. His landscape art explores the Australian experience, questioning our collective fear of place, retribution and fear of existence as drivers of environmentally damaging behaviour, and instead, explores reconnection to our land through retelling of stories and giving space to personal mythic connection to place.

More of Iain’s work can be seen on his web site and Instagram.

Footnote: For those wanting to learn more about the salt printing process Ellie Young’s definitive book The Salt Print Manual is a must read.

Gold Street Studios also runs workshops in salt printing. Editor, View Camera Australia.

Hello Iain

Great to see that you have discovered the salted paper print – You are right – It has the greatest tonal range of any photographic process (provided you processes the negative correctly.) I have never found it necessary to preshrink paper. Double coating the silver can block up the image with a bronzing effect. (sodium chloride can only change only a certain amount of silver nitrate into the image making silver chloride) I am assuming that you are using a fixer (sodium thiosulfate ) after the gold toning – as the image will degrade without the fixer. Light will fog the image turning it grey. And of course, the fixer ( a necessary enemy) requires the clearing agent (sodium sulphite) to assist the removal of the fixer and at least 40 minutes wash to ensure that the salt print has a reasonable stable life.

I hope you continue to enjoy the salt print. Historically and aesthetically it is an important process.

Thanks for the comments Ellie. All great points you make. I should say I am using sodium thiosulphate fixer after the gold toning and sodium sulphite to clear. The reason for pre-shrinking the paper is for registration with the subsequent gum layers using the same negative. Fabriano Artistico shrinks quite a bit compared to other papers of similar weight, like COT 320 which doesn’t really shrink, but it has a wonderful surface texture. I do the double coating of the silver nitrate because I am using a brush, not having mastered a rod yet, but to guard against what you point out I use only 6% strength on each coat.