And the clouds parted, Gangerang Range. Inkjet print I have…

My black & white world by Murray White

My transition from colour film to B&W photography required a step into the unknown. I say unknown in the literal sense, because even the fundamentals of photography as I knew them involved a major reset. But there was a metaphorical step too, where the unknown came to be embedded in my work. The extent to which B&W would impinge on reality, and bring questions without answers, was both unexpected and rewarding.

I think that being able to find the concept and identify a meaning within an image is important to us as viewers. We like to understand what we are looking at and how it fits in with our view of the world. However, I have come to realise that paradoxically, we also enjoy ambiguity and the opportunity to interpret a photograph for meaning, perhaps beyond its most obvious connotation. I find that there is more satisfaction to be had by exploring a simple image for layers of interest, than be overwhelmed by a complex capture devoid of intrigue.

My world of landscape photography shrank almost overnight; not in its compulsion, but in its interpretation. Dramatic and all encompassing views seemed to miss the mark for me (my apologies to Ansel, although he remains an inspiration). Yes, this world does reveal some extraordinary vistas, and yes, their capture does provide for immediate wonder and gratification. However B&W in my view, expresses like no other medium, the magic of intimate and ambiguous subjects.

Complementing this partnership is the view camera. Its large format negatives provide rich image quality, and its movements allow for precise sharpness and the possibility of distortion free captures. Yet for me, the real power of a view camera lies not in its technical capability nor in its intrinsic size, but rather in the simplicity of a large viewing screen for composition. I find that the image layering effect on the ground glass not only implies depth, but breaks the view into individual blocks like a jigsaw.

The ability to really see the image allows for a contemplative approach to photography (well, when it is not windy anyway…) We can slow down and study the elements making up the landscape, not just for what they are, but rather for what they may suggest. Under the dark cloth, faced with an upside down reversed image, the noise of superficial objects becomes subdued, and there is a visual transition into pure shape or form, or the curious juxtaposition of everyday items.

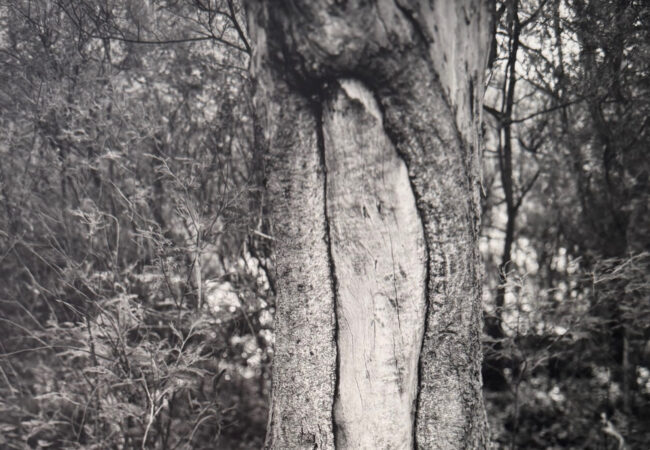

Allowing our minds to wander from an intellectual outlook to a more imaginative platform releases us from the banal and into a world where the possibilities are seemingly endless. Hills appear as waves, trees take on human qualities, rivers are no longer wet and the clouds can be anything that you desire. Our world can transform from being just a pretty subject to an alternative entity with its own apparent meaning. We can become partners with the landscape on its own terms.

Many ancient cultures understood this link; indeed celebrated the relationship. For them the landscape was pivotal to life itself. It offered an essential guide for the living, and was a conduit to the spirits beyond. The natural world revealed its significance in countless and indisputable ways. The seasons played out with predictable returns, spiritual forces were identified and preserved within the landscape, times of abundance were appreciated, while hardship was also attributed to the powers of Nature.

Modern living has somewhat isolated us from these forces, reducing our need to be in tune with the landscape. Many people no longer live physically close to the environment that sustains them, and often find that any spiritual connection to the land remains distant at best.

For me, large format B&W photography is an activity that brings the landscape closer and permits interaction in a meaningful way. Of course interaction hasn’t involved a two way verbal conversation as yet (or even a one way conversation I might add, although I listen with intent….). However, while cocooned under a dark cloth, it is easy to become fully immersed in what is largely, a living subject; sometimes I find it hard not to query whether there is at least some underlying level of consciousness in our surroundings.

So to the image above. It is a simple waterway composition captured on FP4 with an Ebony 4X5 camera and 80mm wide angle lens. The subdued lighting has rendered a shine on the rocks and plenty of detail throughout (if you overlook patches of the water itself). However, for me the setting is only a framework for the main game, where inert players can come to life. Others open to alternative possibilities may also see this image in a more imaginative light.

The water has substance; far from being an odourless, tasteless and shapeless entity, it has structure and meaning. A human form emerges from the lifeless rock, to question the concept of being. Clearly there is no human within the photograph, but its implied presence helps to give life to the landscape itself. I still find myself questioning the gender of this figure, despite knowing that in reality it is simply a random interaction between water and rock.

Serendipity plays a role here too. I wondered how the piece of bark flicking back and forward in time with the water flow would translate in the visual image. As it turned out, yet another figure appeared! Closer inspection of the print revealed animal faces chiseled in rock at the top of the split – not seen by me at the time of exposure, but yet another reason to tune into what could be described as a “living landscape”.

Not all of my recent photographs depict human or animal features so overtly, but many play on the concept. Natural features can imply a conscious state of living by their multiplicity, stature, apparent interaction or any number of other markers of life. Searching and sometimes finding these links to our own world is quite rewarding for me; in the same way as others may gain satisfaction with the successful capture of their own individual photographic projects.

Finding the medium to best reveal your vision is a personal quest, and one that should always be challenged. I have arrived a little late to the B&W revelation, but better late than never! I have found that monochrome fits neatly with my vision and tendency to look for unexpected and alternative juxtapositions within the landscape.

I believe that B&W has more capacity to illustrate ambiguity in the landscape than has colour. Perhaps this is a function of high contrast features, perhaps it is because the shadows transition from shape into form without the abrupt intrusion of colour. Perhaps it is that we tend to look more deeply into a monochromatic landscape simply because of its slightly unsettling characteristics. For the moment, the reasons don’t matter, I remain content to continue exploring the unknown.

Photograph above: Double Cross. Silver gelatin print by Murray White.

Previous Post: View Camera Australia back online

Beautiful Murray – and fine words

Thankyou Ellie