The State Library of Victoria has recently purchased Forest at…

Folio: Mark Darragh

Abstract Realities

Writing about abstraction is perhaps curious for a nature and wildness photographer. In some respects, abstraction seems to run counter to the ethos of Australian wilderness photography which has long been grounded in the Realist tradition of photography.

I chose the title Abstract Realities because the premise of this folio was to explore the notion that a photograph can be at once abstract, while at the same time being a representational depiction of a subject.

Background

As a teenager, starting to explore photography as something beyond a simple memory device, Brett Weston and Minor White were two of the photographers whose work greatly impressed me. Both are noted for their exploration of abstraction and their works are still touchstones for me . Aside from being one of the most influential mid-twentieth century American photographers, White taught and wrote extensively about the philosophy and practice of photography and I often find his observations on the subject insightful. One of his pithy comments about photography and abstraction accompanies his folio, the Fourth Sequence. He says:

“The spring-tight line between reality and the photograph has been stretched relentlessly, but it has not been broken. These abstractions of nature have not left the world of appearances; for to do so is to break the camera’s strongest point—its authenticity.” –Minor White, Fourth Sequence 1950

The monochrome photographs of White and Weston may seem worlds apart from colour, nature and wilderness photography, but even within these genres, photographers have explored abstraction for decades. A contemporary of White and Weston, Eliot Porter pioneered what he coined “the intimate landscape”, and within his wide body of colour work, abstract composition and isolations frequently feature.

In The Color of Wildness (2001), Porter is quoted, “The relationships that are all-important for me in nature photography are best illustrated in my close studies. Close is a relative term; it may refer to a spot of lichen or a reflecting pool of sands, or more broadly in a larger connotation to a sheer cliff or a grove of trees. But in either case the photograph is an abstraction of nature – a fragment isolated from a greater implied whole, missed but imagined, a connection which assists in holding the viewer’s attention.”

Closer to home, amongst Australia’s Wilderness Photographers, Tasmanian Chris Bell has explored elements of abstraction in his work, arguably far more than any of his contemporaries such as Peter Dombrovkis, Ted Mead and Rob Blakers.

The works of all four of these photographers encourage the viewer to think more deeply about both the subject and themselves, whether that be the exploration of light, form and texture in the work of Brett Weston, the concept of Equivalence in the case of Minor White or to appreciate the beauty and complexity of nature and the need for its preservation as in the photographs of Chris Bell and Eliot Porter.

My own practice

My photography developed along with my interest in exploring the nature world and studying ecology and biogeography. That continues to inspire and inform much of my work. Much of my early photography was simply a response beauty and the interaction of light on a subject but over time it has increasingly focused on exploring both the physical and biological nature of a landscape along with the processes and ecological relationships which shape it. In general terms that might include the underlying geology; nature cycles such as nutrient and the water cycle; the impact of weather, climate and season as well as the interaction of different species in a particular environment.

The comments above generally apply to my wider landscapes and photographs that might be described as simple representations and they apply even more so to the close up work which makes up this folio.

Most of the photographs were taken at 1/2 to life-size, in other-words an area of about 8×10” to 4×5”. Unlike small formats, this is large enough to capture not just a single subject such as a flower or leaf but rather what I like to call a micro-habitat. The isolations that feature on this folio build on those general ecological themes and explore processes such entropy, disturbance and decay vs renewal, regeneration and succession.

By focusing on a fragment, excluding context and scale, the photographs are abstracted in the sense of being extracted or removed from the wider landscape, removed also from the typical visual cues that are generally associated with wilderness photography.

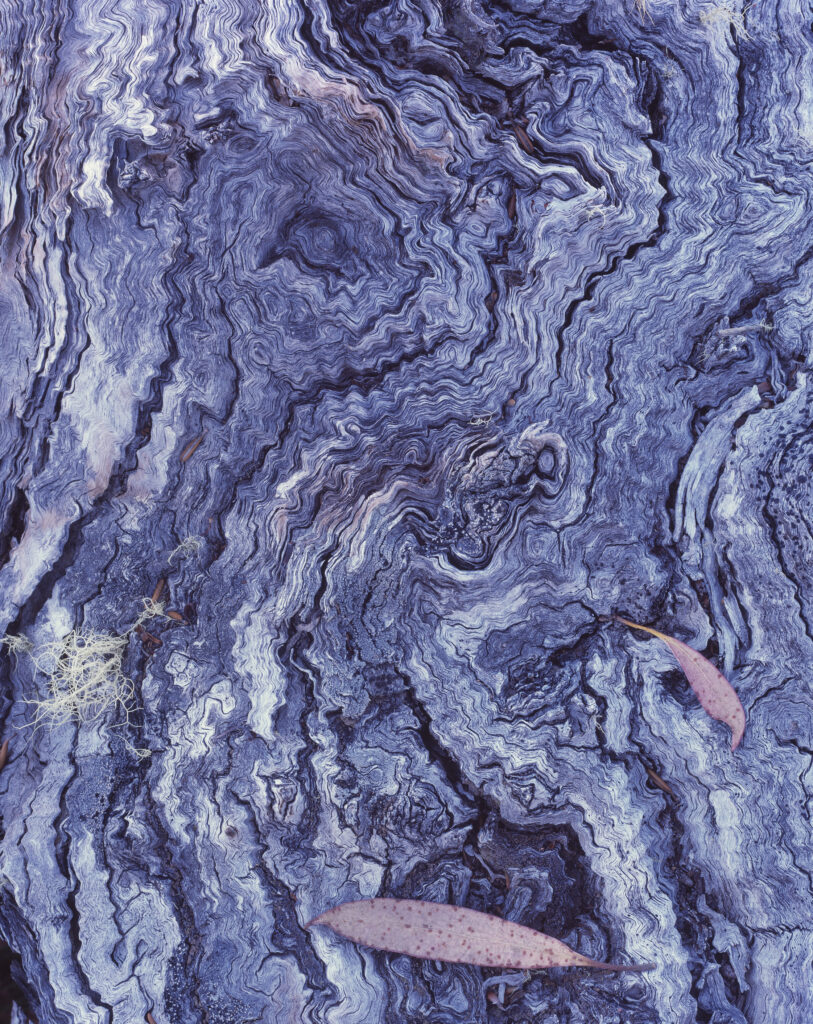

Although aesthetics and science both inform my work, my practice of making photographs is also a very instinctive and what I can only describe as a visceral response. The first image in the series was photographed on Mount Wellington in April 2001. At the time it was very much about photographing a fascinating subject rather than a deliberate attempt to capture something abstract. However, seeing the processed transparencies for the first time it struck me as both ambiguous and abstract, a photograph that managed to transcend being a simple representation. This image became the catalyst for what I have increasingly explored in my photographs in the last twenty years.

The Huxley River rises on the main divide of the Southern Alps and is a typically dynamic environment. In winter and spring, avalanches commonly scour the valley walls, bringing rock down from the glaciated peaks above; snow melt and flooding can also sweep away vegetation along the river banks.

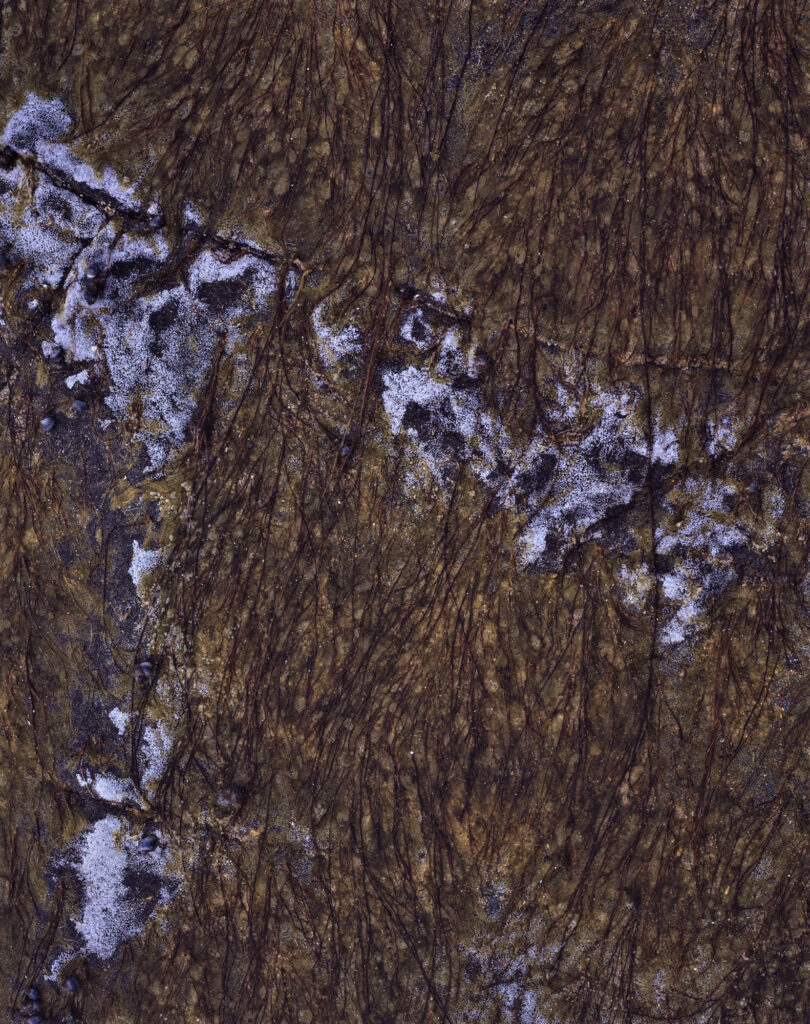

Lichens such those illustrated (above) are typical of life at the margins of so many areas on our planet, in this case on the river side in the upper Huxley Valley. A symbiotic pairing of fungi and algal or Cyanobacteria, Lichens are decomposers but also have the ability to photosynthesis and produce their own food. By secreting chemicals which slowly breakdown rock, they play a role of decomposers but also they are also amongst the first organisms to colonise new environments, realising nutrients and providing a foothold for plants including mosses to eventually establish.

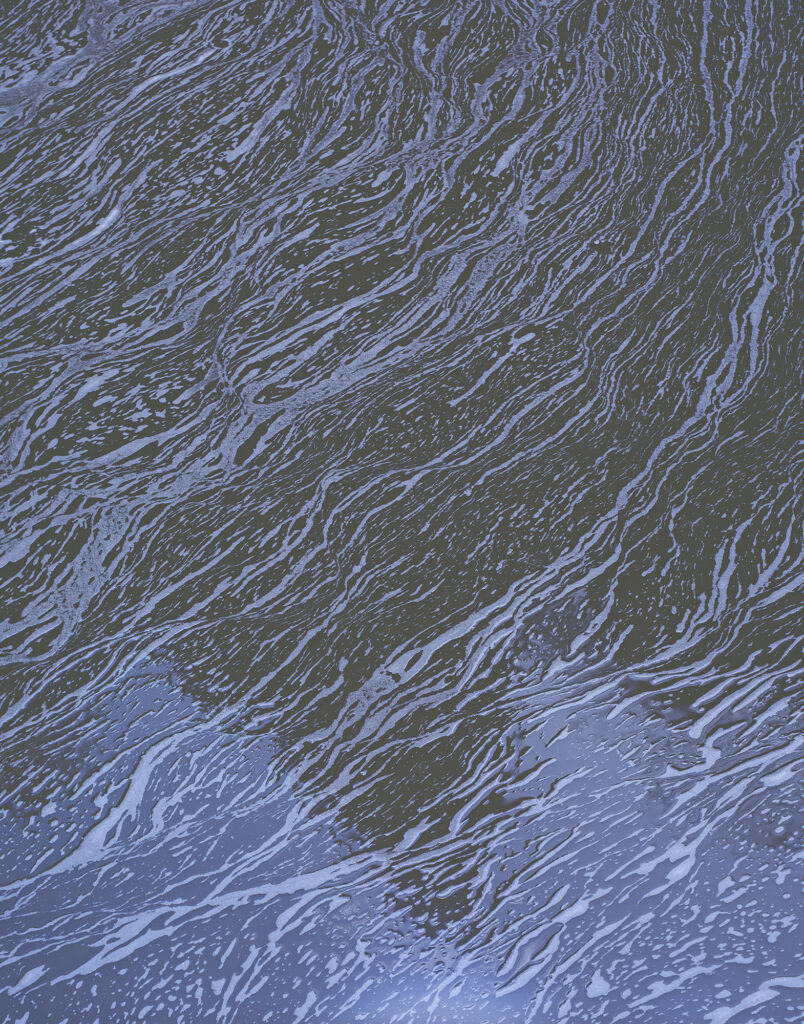

Photographed the following day (main photograph above), just a few hundred metres down river from the lichens, captures the flow of the Huxley River and the reflections of late afternoon light on the glaciated peaks high above the valley. The deep blue colour is due to the glacial flour, the pulverised remains of the mountains themselves. In this photograph I sought to represent the energy and dynamic power of the river, a reminder that water, so fundamental to nourishing and sustaining the landscape, is such a powerful creative and destructive force in the landscape of the southern Alps, whether it be liquid or ice .

Half a days walk down the valley, the gradient and intensity of flow of the river reduces, allowing Beech Forest to grow right to the river bank. Here on the edge of the forest grow Alpine Water Fern and Filmy Ferns (above), both delicate species which depend on the protective canopy of the forest and the moist environment near the river to survive.

Main photograph above: Evening Reflections, Ruataniwha Conservation Park, South Island, New Zealand

“One should not only photograph things for what they are but for what else they are“. Minor White

There is an underlying aesthetic common to all the images in this folio; they are not simply representations, nor photographed with just the intention of abstraction and ambiguity. Rather, they challenge viewer to see something more than a photograph; rather than provide answers, they ask questions. These images capture moments in time, fragments of the landscape which so often go unnoticed and they give a glimpse into the interdependence of life on our planet to which our survival is inexorably linked.

In preparing this folio, I must thank Gary Sauer-Thompson for his valuable insights. A regular contributor to View Camera Australia, Gary has explored the subject of abstraction and photography extensively, both as a photographer and a writer.

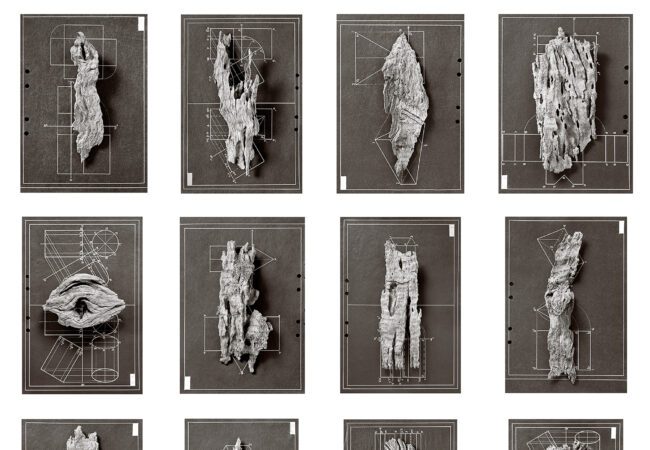

A recent example of this is his online exhibition with Adam Dutkiewicz – Abstraction: different interpretations

Next Post: Exhibition: Into the Blue II

Previous Post: Folio: Mat Hughes

Fine images Mark, precise framing and great use of vertical compositions. Very inspiring.

Thank you, Murray. For me the subject really determines the framing and composition of the final image but often vertical composition does seem to work particularly well for these close-ups.

Sometimes we are so busy running around that we forget to marvel at what’s right under our noses. Fantastic, beautiful work!

I appreciate your comments, Matt. There is a whole world beneath our feet for us to explore as photographers, it’s a privilege to have the opportunity to share a little part of it.

This folio is a superb body of work Mark. You should be very proud of it.

Thank you Gary for your thoughts and encouragement. I hope the discussion spurs some more interest in subject of abstraction and photography.