The Photograph Considered number forty – Geoff Murray

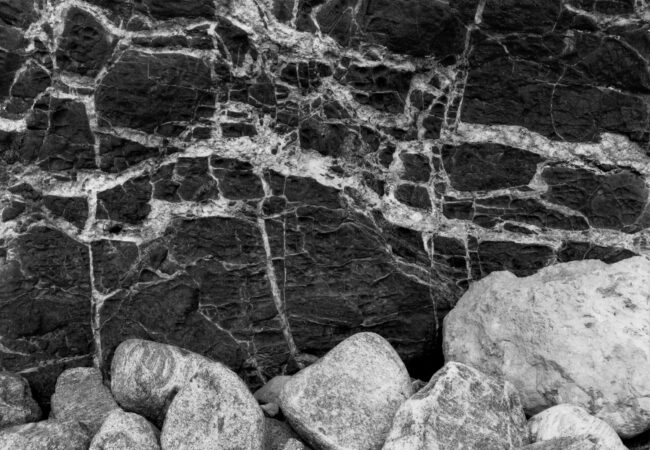

Frozen tarn. Walls of Jerusalem National Park. Tasmania. Colour transparency.

Like most photographers, I have moved through a variety of formats over the years. I first started creating images in the early 1980s, initially with a Pentax K1000 and negative film. Then I discovered Kodachrome, a real ahah! moment as I saw the colours that I had envisaged as I pressed the shutter release.

After a few years using 35mm film, I bought a Mamiya 7 medium format rangefinder, a beautiful camera for wilderness photography. Light, super sharp lenses and a genuine pleasure to use. But, I found controlling depth of field difficult with the longer focal length lenses used in medium format.

I had read about view cameras and their almost magical control over depth of field using the Schiempflug principle and when a friend of mine said he was selling his Horseman VH-R 6×9 view camera I jumped at the chance.

This was a strange animal compared to what I was used to with multiple means of adjustment and tilts, swings and shifts to master. And it was a weighty brick!

I purchased 4 lenses to suit the camera, 65, 100, 150 Schneiders and a 300 Nikkor.

And then I started to learn how to use it.

There are several methods available for adjusting for depth of field with a view camera but the one that I found that suited me best involved having a graduated scale mounted on the rail of the camera. I would adjust the tilts by eye using my loupe on the ground glass to have as much of the image in focus at the same time. With landscape photography it was rare indeed to have everything sharp but it certainly helped having the tilts available.

Once I had achieved the best result using tilts I would then rack the focus out and back to see the distance required from furthest sharp plane to nearest. This would usually only be a few millimetres. Then I would consult my handy scale and read what aperture was required for an acceptably sharp image all over. Moving the rail to place it just rear of centre resulted in a sharp image. This was a very quick process and after awhile I could set my camera focus for most scenes in a couple of minutes.

This particular image presented itself one chilly July morning in the Walls of Jerusalem National Park in 2000. I had camped out the night before and the temperature had dropped to a cool -10°C. As I wandered around looking for images I came across this little alpine tarn that must have been snap frozen to create these remarkable patterns. I have never seen anything like it since.

Using my normal process as described above, I captured a satisfyingly sharp image that represented what I saw before me. I used my 65mm lens (equivalent to a 28mm in 35mm terms) so I could capture the whole scene. My film was Fuji Velvia 50 ASA, a lovely saturated and contrasty film that gave excellent results in the right situation.

Compared to today’s digital cameras with their 14 stops of dynamic range, Velvia had 5 stops of dynamic range so accurate metering was essential. I used a Sekonic spot meter and usually took multiple readings of what seemed to me to be 18% grey then averaged the readings to give my final exposure setting. It usually worked quite well.

I find wilderness photography an opportunistic process. Basically it’s a case of wandering around in a pleasant wilderness environment looking for photographic possibilities. This scene was one that instantly appealed to me as a unique and beautiful location that was worth capturing on film.

I still wander through our magnificent wilderness areas, searching for inspiring images although now it is with a somewhat smaller and more electronic camera. Nevertheless, the creative process is much the same, arranging the composition to give a pleasing result, controlling light and time to produce a worthwhile image. The tools may vary but the result is similar.

More of Geoff’s work can be seen on his website.

Thank you Geoff, great article & photograph.

Thanks for the opportunity to contribute David 🙂