Photographing with an Open Mind What are you photographing? It…

The Photograph Considered number twenty eight – Charles Millen

Leaf & stone, at the throat & precipice of time

I know I should talk about a recent photograph that I have captured, but in terms of my large format photography, I feel that 2016 isn’t long ago at all. Like geological time, my it has been a slow moving process, this is part of the reason why I enjoy it so much. I feel that this photograph was a pivotal moment for me in my large format journey, this image is also my introduction to you the reader, as it galvanised me in terms of the direction that I wanted to take my work and affirmed my love of the process and my commitment to it.

In 2015 our family moved to a small mining town called Pannawonica in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, all the way from Tasmania. I had been working in the mining industry for nearly a decade and had always wanted to spend time photographing in the Pilbara, when the opportunity to live residentially came up we jumped at the chance. My field camera was a big part of my recreational time on my days off, I would load my gear the night before and jump in the car in the early hours of the morning. Most of the time heading to the Robe River and a scattering of mesas just out of town, or I ventured further. About 40 kilometres away, nestled near the northern edge of the Hammersley Range was an area called Bungaroo Creek, which was accessible because of the mining company exploration tracks cut through the ancient valley and creek beds in their tireless search for iron ore. The road was rough, scoured by wet season rains, intersected by creek crossings and populated by numerous kangaroos and snakes of varying sizes and temperaments. Bungaroo was my favourite place to visit with my field camera, the relatively flat valley that was hemmed in by the Hammersley Range afforded almost infinite possibilities for subject matter, the rolling spinifex speckled hills and mesas to the north and the higher, more rugged Hammersley Range to the south. The northern edge of the range, characterised by eroded inlets from millennia of wet season rains, which carved into the oxidising reds and oranges of the layered rock. Snappy gums with their white trunks punctuated the landscape and tempted a keen eye to explore.

One misty morning at the opening of the wet season, I travelled to an area of Bungeroo that I found particularly interesting after passing it several times on previous outings. There were several inlets that looked to recede someway into the range that I really wanted to explore. I parked the car off the track, wandered up onto the first terrace of the range and found a lone snappy gum, clinging onto the edge of the terrace, looking out over the mist shrouded valley. I pondered capturing an image there, snapping a quick photo with my phone for reference and to prompt me to revisit the site again. Hindsight tells me that I should have made that image then and there, I never returned to the same spot and had that wonderfully dense, dark steel blue and grey, low hanging stratocumulus again. I feel a sense of loss for the image I did not capture on that occasion, I have that phone image on my Instagram page to remind me of my carelessness and reluctance to shoot outside of the preconceived idea that already had in my mind. That lesson has taught me to not seek one image or location alone, but to be aware and open to other compositions as I wander along the way.

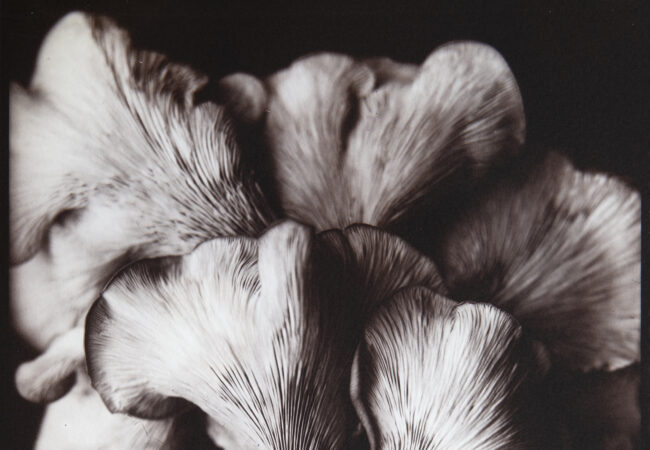

I walked down off the terrace to the inlet and rocky creek bed that led into the range, it was about 100m deep and the walls narrowed as I walked in. Ancient layers of iron ore stone in blue, grey, red and orange around surrounded me, gum trees grew from the walls and hung over inaccessible terraces overhead. When I reached the terminus, a funneled structure presented itself, carved into the wall and rising to the precipice of the inlet, out of sight above. It was about a meter in diameter, a throat that the water flowed, carved and fell through when the wet season rains inundated the range above. I set up the view camera, metered my scene and captured an image, an image which I called ‘Maw’ and also has subsequently never been scanned for one reason or another. I pulled out the dark slide and started about dismantling the set-up. As I was doing so I noticed that at the bottom of the ‘throat’ were stones, erosional remnants littered with gum leaves. They glistened with the moisture from the misty and infrequent showers that had intersected the night and managed to fall through the narrow canyon-like inlet. Straight away I recognised a delicate composition laid out before me, almost deliberate in its arrangement and strangely beautiful, elegant and ornate. I reassembled the camera, attached the 135mm lens which I thought would be the best focal length to fill the frame naturally. It was a surprisingly challenging image to capture, it took some time to get the framing just right without disturbing the stones and leaves (I never interfere with or rearrange anything other than the camera when I am photographing nature). The height of the camera placed the ground glass at a difficult angle and forced a tip toed, hunched dance to add a small amount of tilt and swing before I inserted the dark slide. I made the image and turned my thoughts to home as the wind rose and the mist turned to rain, becoming heavier. The Pilbara can be a dangerous place when the wet season arrives, so I packed up and ventured home, vowing to return sometime to capture the lone snappy gum on that precipice of stone and time. The Bungaroo Creek water table is currently being de-watered at a rate of one million litres a day in preparation for an open cut mining operation. The images in this series which equate to only three or so transparencies I captured (and failed to capture) in the area are all the more poignant due to the fact that the landscape will one day soon, disappear forever. I used to have a blog where I posted my work, I wrote haiku poems that came from the images I captured, the haiku I wrote for this image which I titled ‘Leaf & Stone’ is as follows;

Rain, fall forever.

Wet thy leaf & stone, then grow

& never return.

Sometime later when I had a stock of 30 + exposed sheets, I processed a batch of E6 in the bathroom in Pannawonica, using two thermometers to double check my temperature at all times. I would commence pouring my chemical at about a degree above recommended to allow for temperature fall off as I poured and agitated the daylight tank. I never had any E6 disasters when processing thankfully, and now I ship my exposed sheets in batches of 20 to the U.S. due to the fact that the 1 litre three bath kits are no longer available and I can’t find a reasonably priced lab in Australia. I miss home processing, but I can’t utilise the full yield of the new 2.5 litre kits without stockpiling the exposed sheets for a very long time, and subsequently I would have to process for days to work through that backlog. I predominantly use slide film for simple reasons, I love seeing the end result when I remove the sheets from the tank (or now post pack) and hold them to the light for the first time. I find scanning slide film relatively easy and whenever I have used colour negative film it has required much more time in post to get the colour right. Slide films limited exposure latitude taught me a few hard lessons in the beginning, though I am thankful for them now.

I scan my 4×5 sheets using an Epson V800, spot healing the dust and then I colour correct and apply a high pass filter for sharpening as the final step. I generally print 24×30 inches on Hahnemule William Turner 190gsm textured surface paper and then I take them to Peter to frame for me. I have several prints hanging at home, my wife has two in her office at work and I have sold several 24x30s of an image I captured of Pannawonica Hill which seemed to have resonated with some of the locals there, it became a bit of a default gift for people when they were leaving the town. Leaf & Stone currently only exists in printed form on my Fathers office wall in my parents’ home as a 12×15 print. I am currently looking for an art filing cabinet so that I can print more of my work and store it. Longer term I would like to do my own framing and beyond that, time will tell I guess.

We lived in Pannawonica for two years, the Pilbara has ten lifetimes of inspiration for a nature photographer. Part of me laments the loss of my ability to explore that striking, harsh and beautiful land, whilst the other side of me is excited by the ability to explore my home land of Tasmania more now that we are settled here. Work and family commitments do limit my ability to venture out as much as I would like, I have an ongoing open ended project which is focused on capturing images within a 5 to 10 kilometre stretch of coastline on the northern edge of Tasmania, at the mouth of the Tamar river where we live in a windswept hamlet. I want to challenge myself to continually look for inspiration within the place that I am so familiar with, all the while continuing to learn and grow with my art.

I have no gallery presence and shoot primarily for my own enjoyment, it is a deeply personal and introspective process for me that provides catharsis in a busy world. My Instagram pages are the only places where my large format work appears other than in print. I guess my large format work is a reflection of me, quiet and introverted…

Charles Millen

I was an avid early adopter of crude digital capture on an Apple QuickTake camera in high school, and I processed my composites in an early version of Photoshop. I then completed a Fine Arts degree at the University of Tasmania, again focusing largely on the digital process of image making, sound and video. I felt that as an artist I still hadn’t found my medium, then Photography really came into focus for me after I graduated. Large format photography became prevalent after initially dabbling in 35mm digital & film. A local photographer and picture framer (Peter Clark) alerted me to large format after he loaned me a couple of his medium format cameras, stating that it was, where I was going to end up anyway”. I bought a field camera and three lenses in a kit that came out from the U.S. and I have been shooting predominantly slide film since. The whole process is fun, challenging and has been of course frustrating, sometimes disappointing and other times immensely rewarding when the process comes together and I view that well exposed sheet when I hold it up to the light, or mount the final print on the wall.

that is a gorgeous image Charles