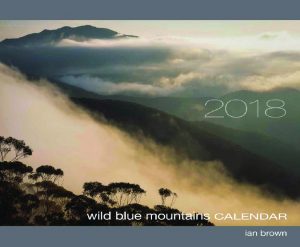

The Photograph Considered number twenty two – Ian Brown

And the clouds parted, Gangerang Range. Inkjet print

I have been bushwalking in the Blue Mountains since my teenage years, and have lived there since 1985. This rich, World Heritage landscape has seen my progressive transformation from a snapshooter with a Trip 35 to a committed semi-professional with a hoard of photographic equipment. Since 2002 this has included an all-metal 4×5 view camera and several lenses. I chose a camera that was both light (2.1 kg is light for a 4 x 5 camera) and rugged so I could carry it into rugged places and give it a hard time. I moved up to large format (from 35mm and medium format) for the image quality, as well as the camera movements. I stick with it now for the same reasons, and I have come to love the process of framing an image.

As a nature photographer I know the Blue Mountains well, and the opportunities offered by the complex and intricate topography, diverse bushland and atmospherics. One visual limitation is that the area is, fundamentally, a plateau…albeit riven with many impressive gorges and cliffs. So your classic landscape panorama is challenged by an almost universally flat horizon. Unusual viewpoints, good skies and horizon-less compositions are helpful to obtaining a variety of images.

On this occasion I humped a pack to a viewpoint I knew out from Kanangra Walls, in Kanangra-Boyd National Park. This is one of the most spectacular parts of the mountains perched on the edge of a great escarpment (which is, in fact, a part of the Great Escarpment). The vista includes some bumpy things along with the usual levelness. I camped the night and drifted off to sleep with dreams of the vast valleys below bathed in stunning dawn light. As often happens, the weather sneered at my expectations with the disdain they deserved.

Next morning I got up in the dark, and the first thing that dawned was my slow realisation that we (me and my several cameras) were locked inside a very thick fog. It looked grim, but ever hopeful, I clambered up onto my intended rocky top, set up my camera and waited, not having much idea what I was pointing it at. It was a nice place, there was no wind, and I guessed I’d eventually get something, even if it was only mist in the tree canopy.

But I didn’t have to wait long. As daylight grew I could see the fog was breaking up to reveal colour from the rising sun. Then all hell broke loose. I don’t always enjoy photographing in the frantic activity of sunrise and sunset, especially using an awkward view camera with gazillions of possible errors (and I’ve made most of them), but the results can be worth the panic. This time I had my insurance (a digital camera) set up on a second tripod. It was all happening so fast I used the digital a lot to make sure I got some results.

The morning turned out to be a stunning visual feast, and I stayed there for hours as the clouds shifted and fell and revealed new aspects of the landscape, with brockenspectres and lots more. I managed to get several satisfying large format exposures and this one was perhaps the happiest. The light and composition just works for me, with the foreground frieze, the overlapping triangles, the shifting clouds and Mount Cloudmaker breaking the horizon.

With 4 x 5 film my 90mm lens was too wide and my next lens of 150mm was a bit tight, but with careful framing it worked OK (must get a 120mm). I rarely record exposure settings but it was probably a mid-range aperture around 16 or 22 because with front tilt the scene didn’t need a lot of depth of field. I worked the exposure from digital camera test shots, an almost foolproof method if you allow for the idiosyncrasies of film. I would have used an ND grad for the sky, and I also tweaked the brightest clouds in post-processing.

As usual for me, the E6 transparency was scanned by a lab on a high-end ‘virtual drum’ scanner to a 476 MB file (2040 ppi, 16 bit), and then I spotted and optimised it with standard photo software. Interestingly, for comparison I once sent a trannie to the US for an expensive drum scan and found no improvement. The main advantage is no dust spots! (as the trannie is floated in oil for drum scanning).

As a 61 x 76 cm inkjet print on cotton rag paper, this image is very sharp. The print has been exhibited several times but never sold and now hangs on my wall. I did use the image on the 2018 cover of my Wild Blue Mountains Calendar.

I love this photo, and cherish the memory of one of my most wonderful mornings in the bush. The fact that it was a surprise, outside my expectations, and that I managed to make the most of it, makes it all the more precious. Aren’t these the times we live photography for?

More of Ian’s work can be seen on his website.

Ian Brown is a nature photographer based in the Blue Mountains, a bushwalker, climber and conservationist. He loves wilderness journeys in far-flung places but more often prowls his local bush for images. His work has been published in numerous magazines, books, calendars, diaries and websites, used in conservation causes and widely exhibited in the Blue Mountains. He publishes the Wild Blue Mountains Calendar and is working on several other publishing projects. His work is represented online by the Light & Shadow Gallery.