Paper bark. Tin Can Bay. 16 x 20 Vandyke Brown…

The Photograph Considered number forty eight – Michael Polychronopoulos

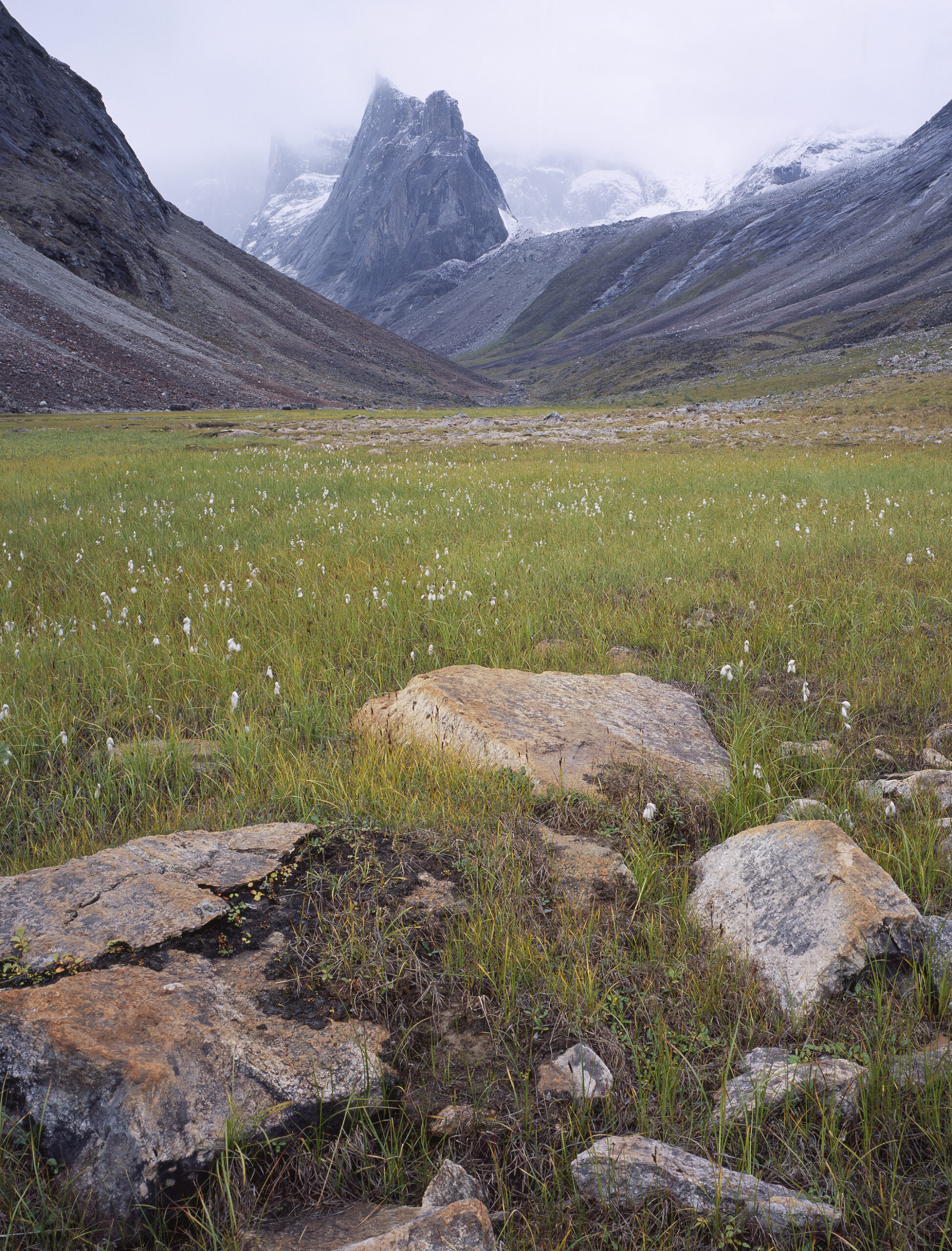

Central Brooks Range, northern Alaska. 2004. 4×5 transparency

I have always been drawn to the erratic lines of wild mountains and natural landscapes, even from a young age when I used to draw scenes inspired by the images I found in National Geographic and other magazines. Once I graduated university as a civil engineer, I had the opportunity to travel and that’s when photography became one of my hobbies. I bought my first camera, a Nikon FE, in 2000. However, the level of detail captured on prints from 35 mm film seemed to be lacking and I wanted larger, crisper images.

In 2001, I was exploring Canada’s west coast over a 10-month period. I was in a bookstore in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, and caught sight of a large book perched high on a shelf against the wall. It was by the Japanese mountain photographer, Shiro Shirahata, and presented colour photos of the Canadian Rockies and glaciated terrain in splendid detail – landscapes that really appealed to me. I was instantly blown away by the images and the sharpness retained in both the foreground and background. The book mentioned Shiro had used the Linhof Technika view camera and 4 x 5 inch fujichrome velvia film.

The discovery of this photographer launched me into an endless pursuit to teach myself how to use a large format camera. QT Luong’s website was an invaluable source for me amongst others. Almost two years later I purchased a Linhof Technika IV and a Rodenstock Grandagon 90 mm lens (equivalent to an angle of view offered by a 24 mm lens I used with the Nikon FE). I exclusively photographed on fujichrome velvia film due to the recommendation from other landscape photographers and adopted a fujifilm quickload film holder to reduce my pack weight instead of carrying multiple double dark cartridges.

I enjoy the entire process of film photography – from setting up a tripod, mounting the camera, levelling, adjusting the front and rear tilts whilst simultaneously observing the inverted image through a loupe onto the ground glass. It forces me to slow down and pay attention to the abstract detail. In the past I occasionally drew landscapes using graphite and attempted to capture as much detail as possible. Photography became an extension to my drawing. What better way to record a landscape than to capture the detail on 4×5 inch film and still have the mental tenacity to carry the loads over varied terrain. I still draw when I have free time and often use my photographs as inspiration.

I have no formal training in photography but have learnt from studying the work of others. Back in the early 2000s, Ansel Adams and Peter Dombrovskis were still very much unknown to me. Instead I was influenced and inspired by Australian photographers Rob Blakers, Chris Bell, and Grant Dixon after travelling to Tasmania for outdoor pursuits. I have also spent time in Canada and Alaska where I was exposed to the photographic work of glaciologist and aerial photographer Austin Post, and cartographer and mountaineer Brad Washburn.

The photograph presented here was taken during a week-long hiking trip at the onset of autumn in 2004, requiring bush plane access into the Central Brooks Range in northern Alaska. The northern limit of the continental forests in North America ends here. You can spend months in this part of the world exploring mountains, rivers and valleys and not see another person. Even grizzly bear densities are low due to limited food sources but mosquitoes are at their peak in the warmer months. If you time it right, you may encounter the hundreds of thousands of porcupine or central arctic caribou on their migration.

The days were getting shorter and colder but there was still close to 20 hours of daylight. On this day, the weather was unstable, alternating between rain and snow with brief calm periods. Small tufts of cotton grass extended along the valley floor towards the prominent peak beyond. The partly submerged granite beneath the moist soil added another texture to the scene. Eons of tumbling rock from the slopes above are buried here. How long should I wait? I also couldn’t drop the bed of the camera completely out from the field of view (something that other photographers had commented about in forums), so I figured I would crop it out in the photograph once it was processed.

The weather appeared to be deteriorating further. I decided to release the lens cable after an inordinate amount of time waiting for a suitable opportunity, and was also conscious of running out of film (quickload fuji velvia film came in sheets of 20 in a box) so I exposed two sheets of the scene. The film was processed in Anchorage, Alaska, and was scanned to a high resolution in Melbourne before being printed on cotton rag paper to a size of 460 mm x 600 mm, which was large enough to appreciate the detail. It was one of a series of photographs I took that year in Alaska across various national parks.

I replaced my linhof technika with an Ebony RW45 camera in 2006 at almost half the weight, but then added weight with a second lens (a fujinon 210 mm lens, offering exceptional sharpness). The attached photo of me was taken in New Zealand and shows the Ebony RW45 at work. A Hasselblad 503 CW medium format camera has also been a favourite of mine and has often accompanied me on numerous trips.

The wildness and expanse of the Alaskan landscape inspired me to return for more exploratory trips, including canoe trips. As with many outdoor pursuits and indeed for those individuals who resonate with the calling of a wild land, there follows immense enjoyment in observing and feeling connected to a remote and wild place. It’s enriching to be a witness and able to record a flicker of time where the dynamic behaviour of a natural system is ever changing. Tracing the irregular haphazard lines of rock stretching into the sky and beyond the horizon, the blankets of snow, ice or vegetation encroaching on a scree slope and the gentle transition of cloud streaming across the sky before morphing into chaotic patterns when an obstruction occurs reminds me to appreciate wild places and the importance of their preservation.

More of Michael’s photographs can be seen on his website and Instagram.

Next Post: Camera Obscura in Fairfield

Previous Post: Folio: Robert Poole