CatLABS is a US film camera equipment store and distributor,…

Making & printing from tone separations by Andy Cross

The title of this article will probably have many people guessing what tone separations are. In a previous article on the Bermpohl colour separation camera the prospects of recreating a full colour image from three colour separation negatives made on B&W panchromatic film was discussed.

This article is a method of printing in B&W when the photographer is faced with very large subject luminance ranges. Before I continue I should elaborate on what a subject luminance range actually is. Subjects do not have a subject brightness range or an EV range or a contrast. They have a subject luminance range. This SLR ( not to be confused with single lens reflex ) is influenced largely by two factors. The first is the amount of light incident on the subject. The second is the surface efficiency of the subjects themselves.

The quantity of light incident on the subject determines how much light is available for the subject to reflect back to the camera lens. Replace a 500w light with a 2000w light and there is four times the amount of light available for the lit side of the subject to reflect. The shadow side of the subject remains at a constant level of illumination because light does not go around corners. Consequently as the amount of light increases the SLR increases.

A subject with a surface like black velvet has a very low surface efficiency and cannot reflect very much light as opposed to a piece of white polished glass which has a very high surface efficiency. Placing a piece of white polished glass on a piece of black velvet will deliver a high SLR irrespective of the amount of light it’s being illuminated by.

Regardless of the subject luminance range it has to be tamed down or in some cases increased to fit onto a negative whose NDR or negative density range and contrast does not exceed the limitations of the reproduction process. In spite of belief to the contrary the printable density ranges of most processes is very similar. Approximately 5 stops. However this includes the specular highlights which remain paper stock white and the maximum effective black for the shadows. In order to retain some tone in the highlights they need to be at least one third of a stop denser than paper stock white while for the shadows about one third of a stop lighter than D-Max. This makes for a printable density range of 4 and one third stops.

This is where the old adage of expose for the shadows and develop for the highlights comes from. Once the SLR exceeds the printable NDR with normal exposure and development times we often hear photographers use terms like I had to pull process the negative 1 stop. Essentially increasing the exposure indicated by the meter and reducing the gamma of development by the appropriate amount. This works fine up to a point when sheet film cameras are being used. Compromises have to be made when subjecting the rest of the images on a roll film to this procedure.

Even on sheet film regular pull processing has its limitations and once more than 1 and a half stops are required photographers will often turn to using funny developers like pyro. Using compensating developers as they are known can work wonders. However I have noticed one thing extreme pull processing will often do and that is reduce tonal separation. People will often use terms like the print looks flat or has a muddy appearance. This is what happens when the limits of the negative exposure and development is reached.

The cure for the lack of tonal separation is to print on a harder grade of paper which increases the tonal separation between values of mid-grey and black but not between mid-grey and the highlights. This in turn begins to block up the shadows. Sometimes this requires the shadows to be dodged which in many respects negates the pull processing. However there are other options. One is to use silver masking techniques known as a CRM or contrast reduction masking. This works well to replace dodging and burning in when the limits of the film haven’t been reached. But they will often have to be combined with other masking techniques like SCIM’s or shadow contrast increasing masks when they have.

Another technique is to first recognize that the subject luminance range is well beyond the recordable limits on the film and shoot a series of tone separations. Essentially record the shadow, mid-tone and highlight detail as a series of bracketed exposures on three rolls of film. Each roll can then be processed to a similar level of contrast. All the information is there it just needs to be correlated and printed onto one sheet of paper.

Before a photographer can wade in hip deep there is a little bit of testing to do because this process cannot be done by trial and error as basic silver gelatin printing can be. Essentially just recording the shadow details, at the expense of sacrificing mid-tone and highlight detail, is similar to photographing a low subject luminance range covering only 3 stops.

With a long exposure time and low tonal values the gamma of development usually needs to be increased therefore increasing the contrast. This will offset the necessity to print on a high grade paper to maintain good tonal separation.

Establishing an exposure and development resume for a series of mid-tones should be very similar to the speed point and development times you are using now for average SLR’s. Another for high key low SLR’s will probably need to be found and reducing the gamma of development will be necessary to prevent the upper values from merging into paper stock white.

The test subjects I used for doing this was a series of dark grey and black beach towels of increasing density including a piece of black velvet. The lighting was outdoors in fairly dense shade under a tree. The exposure time on 100iso film taken as a reflective value off an 18% grey card was 1 second. Select a mid-range aperture for the lens being used. Considerations for reciprocity failure for your chosen film should also be taken into account. Clip tests were carried out increasing the degree of development until I had negatives that printed well on a grade 2½ paper so that I could see the texture of the toweling in all but the D-Max.

A similar test was carried out for the high key subjects. I just replaced some of the towels with progressively lighter ones with the brightest being a sheet of inkjet paper. The lighting was in well-lit open shade. The exposure at the same aperture was 60th of a second indicated by a reflective reading taken from an 18% grey card. Clip tests were carried out altering the gamma of development until I had negatives that printed well on a grade 2 paper so that I could see the texture of the toweling with only the inkjet paper printing paper stock white.

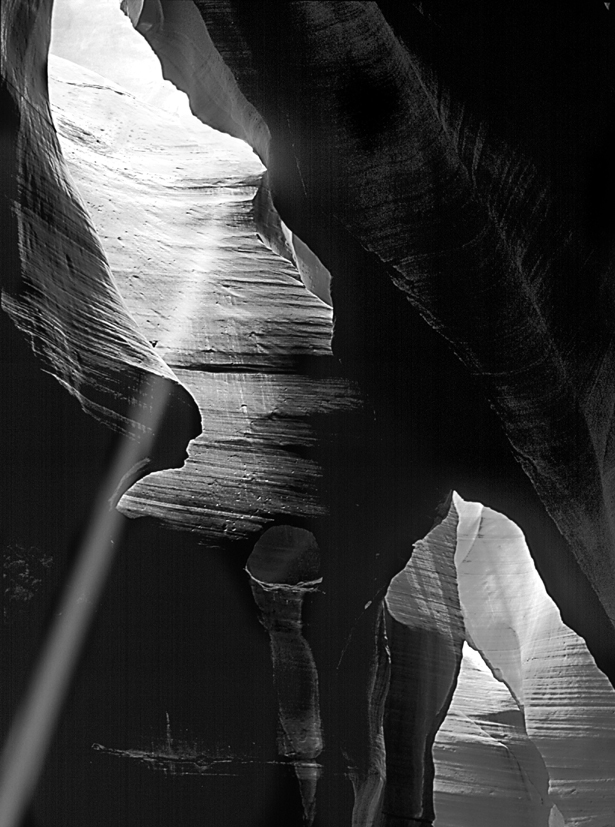

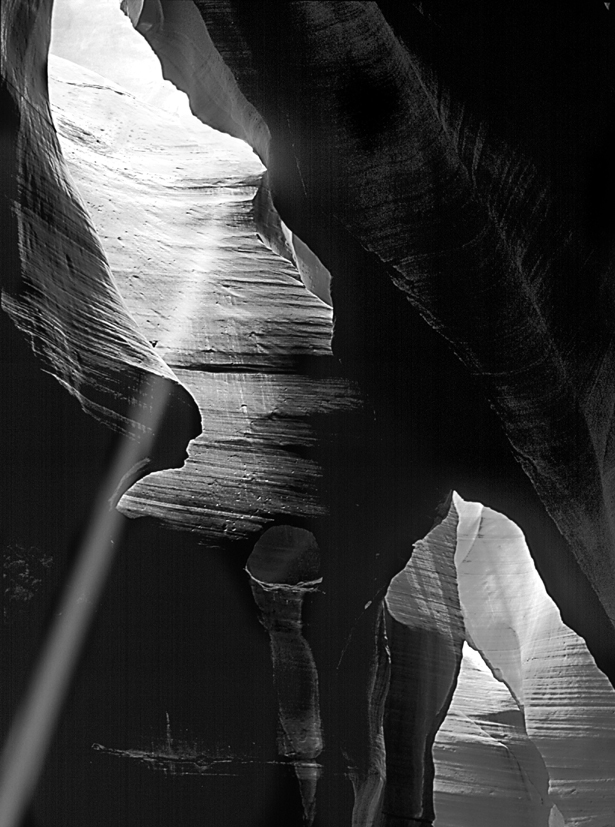

Armed with this information I was ready to tackle difficult to photograph subjects like the slot canyons in Arizona which I was told by reliable people that you can get subject luminance ranges as high as 13 stops when the direct sunlight enters at certain times of the day. How I managed to overcome this issue when shooting colour is a story for another time but I needed to do that as well if I were to make dye transfer prints.

A tripod is essential for this type of photography when it comes to registering the images for printing later on. The requirements of the tripod are greater than normally required for supporting a camera and lens of the weight you intend mounting on it. The locks should offer no movement when the film magazines or holders are changed. Unfortunately lightweight easy to carry tripod and head systems are not the order of the day.

When it comes to actually applying the data you obtained from the testing I first measure the maximum subject luminance range I want to hold some tone or texture in. So you can discount the areas of the subject you want to become specular or D-Max. Calculate how many stops this spans. Divide this EV range into three separate zones one for shadows another two for the mid-tones and highlights.

Bracket at least three shots within the shadow EV range. Another three for the mid-tones and highlights. The shadow exposures should be on one roll of film with the mid-tones and highlights on recorded on their individual rolls. Adjust the exposures using the shutter speeds only. Altering the lens apertures will result in variations in the image size for reasons I won’t go into here. If intermediate shutter speeds aren’t available on your equipment the small adjustments in exposure can be made by using neutral density filters. A third of a stop equates to a ND filter of 0.10 log units of opacity.

The films should then be processed for the same development times that produced matching contrasts on the tests. You will finish up with a minimum of 9 negatives in all. Now comes the tricky part. The negatives have to be printed in register one after another on the one sheet of paper. In order to do that the negatives need to be register punched.

A word about registration punches and registration systems. I use the condit system of punches, contact printing frames, negative carriers and pin bars. Condit went out of business some time ago. Alister Inglis in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada continues to make components that match the existing condit equipment. His products are available through B&H Photo in the USA. You can also find these systems on web sites like eBay. There were other systems around at the time. Anyone with basic engineering skills will be able to copy them. The Durst multigraph enlarger had a pin registered negative carrier but finding the matching punch could be difficult.

Tone separations are printed from the thinnest negatives first progressing through to the densest slowly building up the print density with each exposure. To register them I begin with taping down and punching the thinnest negative on the clear base that the punch is attached to because it is easier to see the next densest negative when placed on top of it. I check the alignment using 10x loupe When the next negative is aligned I tape the negative on top of it and punch the second piece of film. This top film is removed but the first negative left in place. The next densest negative is then aligned and punched. This process is then repeated until all tone separation negatives are registered with the first.

It is advisable to do an alignment test before the real printing begins. I do this by finding the minimum exposure time necessary to achieve maximum black usually by testing from the film base. With the first negative placed on the pins in the negative carrier I use one third of this exposure time to print the negative. I remove it from the negative carrier and replace it with the next. Continue this process and print the third negative. If any blurring is evident in the processed print then re-punching the out of register negatives will be necessary.

When printing this many images you will have 18 surfaces to keep clean. Some people use fluid immersion negative carriers that have register pins fitted to them. But I usually find using them unnecessary. I only use them when dealing with films that have small scratches and other defects on them.

Once the films are registered the printing process can begin. Place the negatives into the enlargers negative carrier on the pins beginning with the thinnest negative first. This will be the exposure that recorded the brightest highlights only. I begin with a base time of one third of one third of the minimum exposure time needed to produce maximum black determined from the previous test.

I use this because of the law of averages. The three highlight negatives combined should make up, theoretically, one third of the total print density. Each set of tone separations one third of that. The same deal applies to the mid-tone and shadow separations. These exposure times will have to be fine-tuned along with the paper grade later on. Print all exposures on the same paper grade. Select a mid-paper grade of around 2 to 2½ .

In order to get a smooth transition from one separation to the next you will probably need to expose two negatives at a time to the paper. Take the first two from the highlights. These will be the thinnest negatives because they only record the brightest highlights and the rest of the negative is well underexposed. Place the thinnest of the two on the bottom of the stack. After making the exposure remove the bottom negative. The upper negative goes to the bottom and the next in the sequence placed on top. The process is repeated until the last negative which is the densest is printed. This negative will be quite over exposed because it records the deepest shadows.

Examine the print. Are the highlights, mid-tones and shadows printed to the correct density? If the highlights are still too light and the mid-tones too dense clip some of the exposure time from the mid-tones and add it to the highlight exposure and vice versa. The same applies in adjusting the exposure between mid-tones and shadows. If after making exposure ratio adjustments between mid-tones and shadows you find the shadows blocking up lower the paper grade. The opposite equally applies.

Making the final adjustments can take some time but keeping careful notes will allow more prints to be made in a relatively short time. The beauty of printing this way is that in spite of the large subject luminance range burning in and dodging, flashing and split grade printing is eliminated.

I have been asked why do this at all. Just bracket the shots in 1/3 stop increments, scan the negatives and merge to HDR. My usual response to that question is. The best FX should never look like FX. This is something a technician at ILM told me once. FX is the technical jargon the motion picture gurus use to describe special effects. I have always noticed that images assembled using merge to HDR always looked like they were merged to HDR. Some people actually like the signature it creates. I don’t.

Another option was to shoot digitally with my phase one capture back. Then merge to HDR and write a new negative on the film recorder. The manufacturers claim a dynamic range on these backs of 12 stops. I don’t know what method of testing they use to determine this but it doesn’t relate to how I use the back. At best its useable density range covers 7 stops which is what can be obtained from a C-41 colour negative.

I did take some of the images on delta 3200 which was pulled processed up to 5 stops in a severe type of pyro developer. Only the shots up to 3½ pull processed actually maintained the tonal separation I wanted. These images illustrating this article were all printed from tone separations.

This technique isn’t for everyone. But I have found it to be very useful when facing quite large subject luminance ranges that exceed the useable limitations of films and processing. The human eye can retain detail when our eyes scan subjects over a range of 20 stops. If they haven’t developed a film or capture device that can achieve the same by now the chances are they never will.

I remember asking an emulsion chemist at Rochester many years ago why we were still limited to recording images with such a small useable density range. His reply was the image formed on the retina is sent to a computer so powerful it is aware of its own existence. I hadn’t thought about it like that. So we might be waiting a while for that 20 stop film or capture device.

Previous Post: Friends of Photography Group 2015-2021