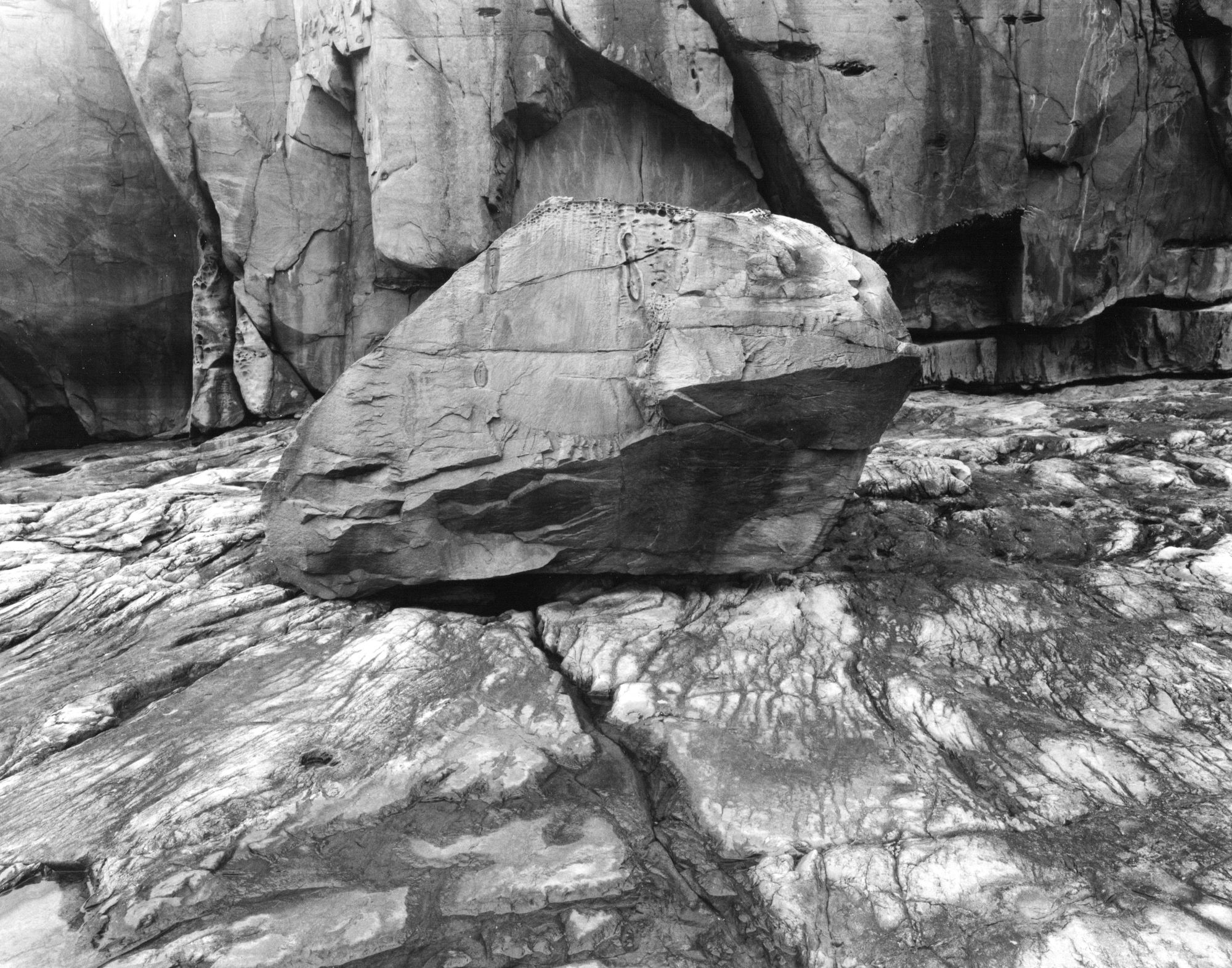

Alex Bond, Bannister Creek Perth 2017, silver gelatin photograph So…

Destination Kiama – part two – The Sapphire Coast – Murray White

Like many other visitors to the beaches of NSW, our enthusiasm to reach the fabled Sapphire Coast surely confirmed that destination marketing remains alive and well in the south east corner of Australia. Before the ocean had even revealed its mystical azure sparkle we felt comforted and somewhat intrigued by an implied reference to its jewel like qualities; maybe not the open wealth and glitter of diamonds, but a more subtle glow, sustained by quieter pride and grounded contentment.

Given that this area’s European heritage traces an earthy path from whaling fleets and frontier country logging, to commercial fishing and rural enterprise, it is not surprising that a pioneering spirit still lingers, permeating the townships here from Eden to Bermagui with a traditional village atmosphere of resourcefulness. Perhaps too, its relative isolation from Sydney (and Melbourne) has been a buffer to the haste of a contemporary lifestyle, helping to maintain an undeniable sense of ‘olde worlde’ purpose and community.

But whatever the reasons for this area’s provincial identity, there is no doubting the power of their effect. Retirees and tourists alike congregate here in healthy numbers to either enjoy a laid back experience of temperate weather and mountainous icecreams, or to be invigorated by its coastal vibrance. New to these possibilities, and unsure of our capabilities, Ana and I pitched for both options; we would begin the day with energetic excitement, then allow Nature to take its inevitable course.

Photographically, there is more on offer here than could reasonably be pursued by one individual in just a short visit. The historic wharf precincts and village or town streetscapes would apply considerable pressure to your film stocks if every photographic possibility was explored. Even the newer harbour areas with their various fishing activities are similarly enticing and extensive, not to mention the magnetic attraction of boats, coastal wildlife, lighthouses and the squeamish experience that accompanies a visit to one of the abandoned whaling sites.

My photographic interest lies only in natural landscapes, so for me it was easy to disregard other potential genres. However even under this restrictive regime, I still found that I needed to narrow my focus if I was to approach subjects and their settings in any considered way. I suspect we all at some stage realise that our most serious and rewarding moments behind a camera are often those spent identifying and then following a particular visual narrative that is meaningful to us. Many enthusiasts speak of the need for a project, the desire to undertake a specific challenge and search for a cohesive visual response, rather than settle for a random and opportunistic grab.

Of course this mode of thinking need not preclude more novel approaches to a chosen subject, or even the selection of an unexpected subject. I often head off on an unorthodox pathway based solely on finding and possibly pursuing a chance combination of light, subject and setting. For example I might be looking at a particular scene trying to visually arrange its architecture to fit in a 4 x 5 box, and in the process of composing notice the sun’s glare from a pool of water. I could shift slightly to remove that glare and continue my ‘planned’ approach, or I could follow that diversion down its own rabbit hole; the diversion then becomes the primary subject. And so on.

The first of those rabbit holes for me in NSW were found at Nadgee Nature Reserve; a coastal wilderness reserve with limited vehicle access, but compensated for by a lengthy remote area walk for those with sufficient experience to take on the not insignificant challenge. In the absence of both time and confidence, we chose instead to visit the northern part of Nadgee via the quiet fishing community of Wonboyn, and other than two tradies rebuilding the fire damaged toilet facility at Bay Cliff, saw not another soul in our time walking along the beach of Disaster Bay.

The headland and beach at Greenglades was our first taste of the Sapphire Coast, but it was the imposing bluff and pounding waves at Bay Cliff that finally convinced me to set up the view camera. I think the compelling combination of isolation, the need to explore rather than follow a pathway and some impressive natural features were in the end, too hard to resist. Other local destinations maintained our sense of visual, and indeed environmental curiosity. Nearby Beowa National Park (previously known as Ben Boyd NP) was especially appealing, with sheltered camping and rewarding landscapes to be found at both Bittangabee Bay and Saltwater Creek.

Dominant rock platforms battered by an incessant ocean attack feature at both camps, with Saltwater Creek also home to a lovely lagoon and beach front. While access to these camps is a little more tedious than some other destinations further north along the coast, we found the relative solitude and lack of those ubiquitous signposted ‘viewpoints’ to be a refreshing change from other more developed parts of the coast. Again, a somewhat lengthy walking track will tempt some to follow the coast from Green Cape Lighthouse to Boyds Tower in the north, although less energetic visitors can certainly walk individual sections as they see fit.

Beowa NP extends north of Eden as well, with no camping areas, but a number of worthwhile turn offs between The Pinnacles (delicate and colourful formations, but limited opportunities for photography unfortunately) and Haycock Point. Our pick for the don’t miss destination in Beowa was Pulpit Rock near Green Cape in the south; an enormous gash gouged into the cliff face revealing solid rock formations that would dwarf a house, yet fine detail almost too small and intricate for the eye to appreciate.

Further north beyond Merimbula and the urbanised growth area of Tura Beach, lies Bournda Lagoon and its popular camping area at Hobart Beach. We found this to be a great camp from which to explore the waterways and beaches of Bournda National Park. There are plenty of walking track options from here that visit secluded headlands and pebble fringed bays.

It is worth mentioning that not all of this area’s photogenic features are hidden a day’s march away in remote parts of the national parks. I found some interesting coastline at Boydtown, just south of Eden, where a late afternoon stroll from the caravan park revealed any number of potential subjects. Even the front beach at Tathra backs onto some imposing headland, and formations that are deserving of closer scrutiny under sympathetic lighting.

Tathra as it turned out, was also our place of peak camping fees. As late afternoon walk ins, we were quoted $81 for an unpowered site for one night, and this outside of public or local school holidays. Now I understand the pressures of wages, amenity upgrades and rising public liability insurance premiums, but in terms of risk, I had no intention of doing a Neil Armstrong impersonation on the jumping castle, and I certainly wasn’t planning to walk the plank on whatever scale model pirate ship lay scuttled at their aquatic centre.

So I respectfully declined the offer of becoming a transient shareholder, and through the magic of our free market economy found another nearby park requesting $45 for the same grassy plot and hospitality. I’m not sure that Ana saw this outcome in quite the same way as myself, but in the fading light as we contemplated the next leg of our journey, I calculated we had just saved enough money to buy another three rolls of film.

Part one can be seen here.

Previous Post: Exhibition: Canberra Contemporary Photographic Prize 2024