What’s a film recorder ? Oops maybe I should back…

Exhibition review – This Vanishing World – Charles Millen

This Vanishing World – Wilderness Revealed Through the lens of Olegas Truchanas. Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston until 16 February 2025.

As you enter the relatively new QVMAG at Inveresk in Launceston, one is confronted by an array of displays full of oddities that range from the ancient world to more recent times. Ascending the stairs, eyes wander from the obscurities below to the wilderness photography of Olegas Truchanas, a Lithuania born photographer who emigrated to Tasmania in the mid-20th Century. Falling in love with his new home and documenting the wilderness, Olegas gave light to the unseen wilds, bringing them into the public consciousness. The impact of the work that Olegas produced during his expeditions is extraordinary, not only showcasing the beauty of the untamed wilderness, but the importance of conserving those places. The work can be described as sublime to put it simply, though a far deeper analysis is warranted and deserved. The exhibition is arranged with care to show the works in a way that is befitting, and complimented with information panels and cabinets contain items of interest and projected image slideshows.

The works inhabit the gallery in a sweeping arc that take the observer on a visual expedition through the lens of a master bushman and photographer. Spotlights highlight each image, hanging alone as an individual work, with some smaller works grouped in pairs. A screen projects works at the western end of the gallery, no doubt a nod to the past slide shows that Olegas hosted and became renowned for. One can walk through the gallery, immersed in the very wilderness that he traversed. There is an image for everyone here, from grand vistas to detailed studies of fungi and flowers, and even an aerial view of Federation Peak (which certainly captivated me for some time).

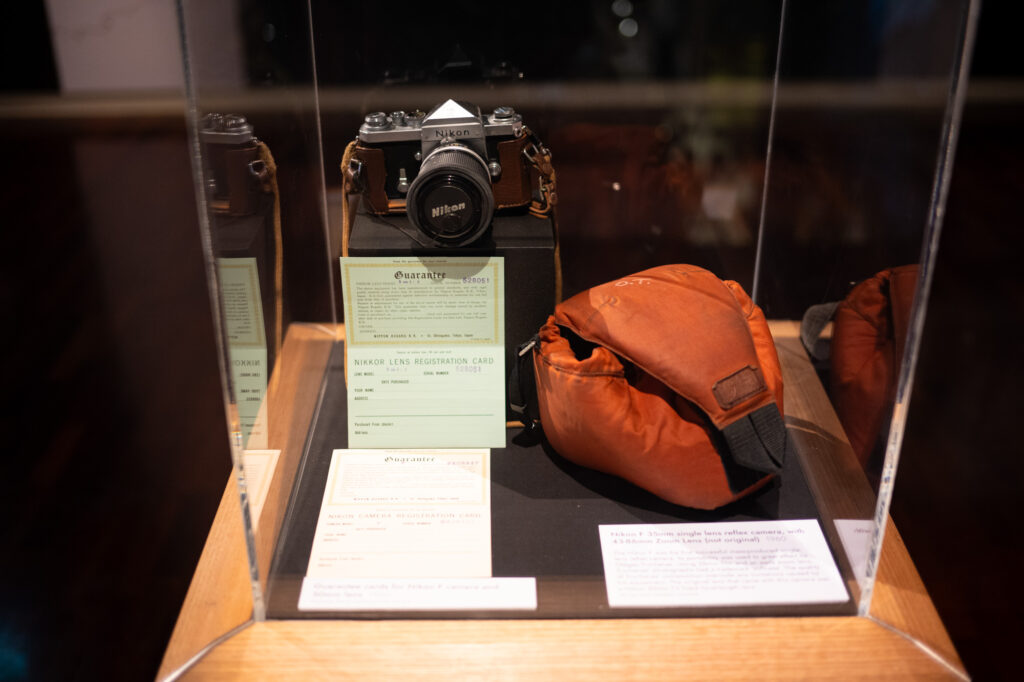

Some of the images in the exhibition I have seen, and they have become iconic over time. To my delight many of the images I have not seen before, including the black and white series at the eastern end of the gallery. Those iconic images of course remain so, and the rest of the works sit alongside those iconic works in equal standing. The creative eye of Truchanas is quite extraordinary and cannot be overstated, a plethora of compositions adorn the gallery. Each work beckoning and enticing the observer inwards. Forest, mountain, river and stone, so much is represented here with drama and majesty. Light of course being a key ingredient and always a dramatic element in Truchanas’ work. Light that traverses the mountains that hem Lake Pedder, or a particular image of the Western Arthur Range skyline that is shown in backlit splendour, with just a hint of the lake below that beckons the observer to contemplate just how spectacular the region is. The light casts down in shafts, highlighting the ridges as they fade away into the brilliance. The image reminds me of Peter Dombrovskis’ ‘Western Arthur Range and Lake Oberon’, almost surely influenced by the deft hand of Olegas and although different images in many ways, alike in the resolute compositional mastery. View to Lots Wife is an image that has a direct lineage that can be drawn to Dombrovskis’ version which was published in 1996, I suspect that it was a homage to his friend and mentor Olegas, captured from the same location. Truchanas photographed with a Nikon F2 35mm camera, predominantly on slide film (with the obvious end to project the images). The way that the 35mm format renders the works gives Truchanas’ images a distinctive aesthetic that permeates every frame. I note that the added speed of responsiveness to fleeting drama that is far faster than that of a large format photographer, and a self-deprecating smile breaks through. The aerial photograph of Federation Peak at Sunset is a prime example, as unique and dramatic image of wilderness that I have ever seen, the landscape below like a diorama, with shadow encroaching, emphasising the jagged peaks, stage like lighting completing the grand spectacle below.

People are notably absent from most of the images on display, aside from a handful that cycle in the projections. One particularly iconic image absent (unless it was cycled on one of the projections and I missed it). A photograph of Truchanas’ three children at Lake Pedder. What makes this image so poignant is the fact that Lake Pedder was flooded a mere month after that photograph was captured, the three children holding hands, reflected in the water underfoot. That combined with the striking compliment of the surrounding landscape with the children, wearing their bright red and blue jumpers and holding the hands of the youngest as he looks downwards into the water. It is an image that is as haunting as it is beautiful. That image would have had the same impact as Dombrovskis’ ‘Rock Island Bend’ (pivotal in the campaign against the damming of the Franklin) had it been shown far and wide in a similar manner. Another work shows Truchanas’ tent, precariously perched in the Frankland Range in conditions that look equally precarious, a visual testament to his mastery and command of his abilities. These skills of the wilderness are achievement enough, but here the prowess of Truchanas’ image making stands tall, encapsulating the essence of wilderness with a deft expertise that should fill any photographer, be they aspiring, amateur or professional with wonder and amazement. These skills are Truchanas’ brushstrokes, all in the service of the image.

The Vanishing World is a treasure trove of works and worthy of a visit(s) to ponder, and to think upon the wider impact of Truchanas’ work not only as art but also as tools for conservation. These works represent the beginning of a style of photography that continues today, and the influence that Truchanas’ work has had is nothing short of profound. The opening of the public consciousness to the realities of industrial encroachment on our wilderness and the importance of conserving it. Olegas gave a visual definition and voice to our wild places, not unlike Ansel Adams in the United States who brought images of profound natural beauty to light, influencing the conservation movements that helped with the establishment of numerous national parks. Truchanas’ work has had similar influence in Tasmania, forging a conservation movement that no doubt saved many of a natural wonder from destruction. Not all was saved and no doubt a moment of profound loss for Olegas was the loss of Lake Pedder to flooding. This did not halt him in his path, as he pushed forwards onto the next front to continue his work, until his tragic death in 1972 on the Gordon River. These are works that have influence on photographers today, who also see the need to raise awareness of just how precious our wild places are. These images illuminate the treasures that we have around us, and cast a light of lamentation on some that have been lost forever.

Conservation aside, this body of work leaves a high watermark for all who aspire to create imagery in our wilderness. The extraordinary, rugged beauty of it all, captured here so eloquently, displayed in pools of light above the oddities below. Mirroring the oddity of the modern world perhaps, showing us nature without pretention or interference from the human hand. Compositions that are natural and free from convolution, waking the distracted modern mind to the beauty of what was lost, and what has not yet been lost, but is indeed at great risk. Truchanas’ work is perhaps as relevant as ever, casting a bright light on what great photography looks like, whilst concurrently casting a shadow of foreboding and warning of what happens when the industrial world and wilderness collide. Truchanas’ works easily hang amongst the pantheon of the worlds great photographers, an exhibition of imagery that forged and encapsulated the iconic Tasmanian wilderness aesthetic that we are all indebted to and admire so much. Not only gifting us with so much of his own work, but also mentoring another of Australia’s great wilderness photographers, the aforementioned Peter Dombrovskis. I would also have to say a mentor to so many photographers that have come since. I know personally I am indebted to the works of Truchanas, a photographer of great influence. It is impossible not to admire the depth of his work and the vigour of its presence, undiminished by time.

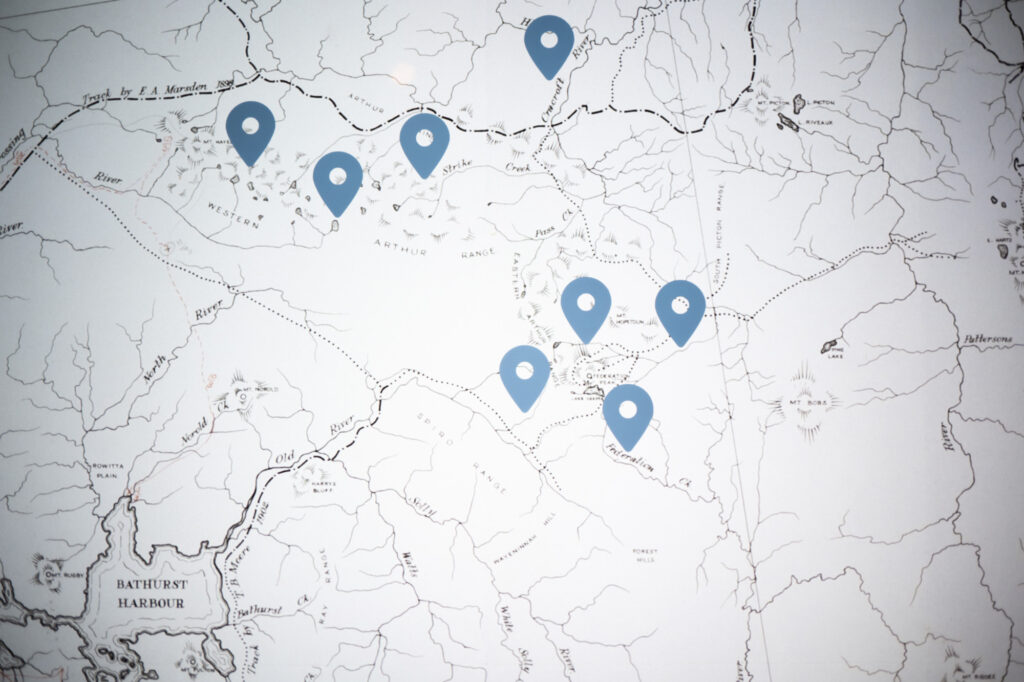

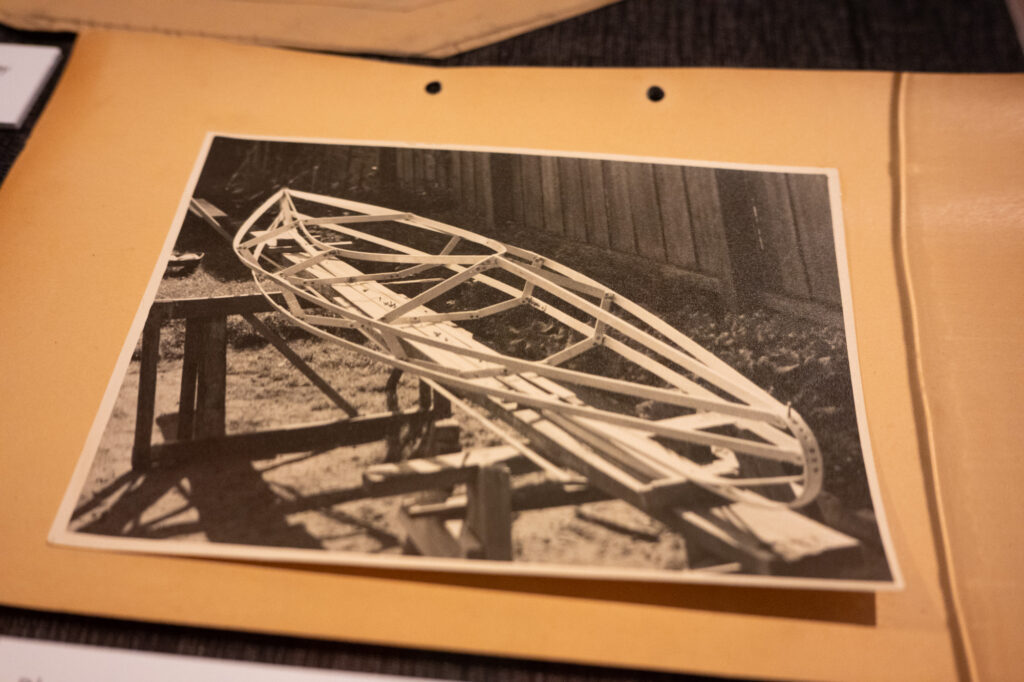

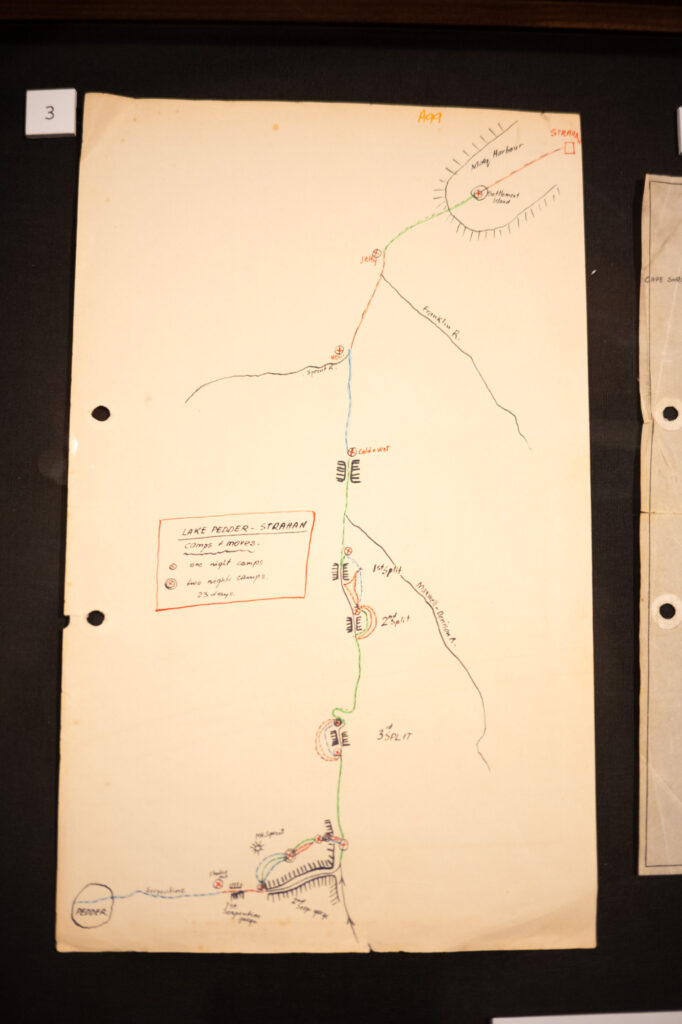

The interactive map of the locations that Olegas explored is a nice touch, alongside his plans for a collapsible canoe, the canoe itself, lists of items needed for his journeys, hand drawn maps, and of course his Nikon F. These items provide insight into the innerworkings of a photographic process that required so much dedication, bravery and of course creativity. I had to smile when I perused these items on display, they broke up the walk around the gallery, providing a moment of emotional whimsy, compared to the intensity felt when walking through the wilds on display here. Intensity that reached a crescendo when my gaze fell upon the black and white series, spaced out on a black wall at the eastern end of the gallery. Another highlight of the exhibition for me without a doubt are these high contrast, bold and dramatic studies of our wilderness.

The tripping of the shutter and creation of a successful photograph is the culmination of the works prior that a photographer has created, sometimes which heartbreakingly end in error, mediocrity or plain obscurity. This is a mountain that an aspiring photographer must constantly climb and overcome, I say this because it is worth mentioning that most of Truchanas’ works were lost to a house fire, a devastation that would throw many into a permanent state of malcontent. Instead Olegas sought to rebuild his portfolio, of which is on display here. Truchanas has gifted us with this body of work that is as relevant today as it was when he was alive. Perhaps even more so, considering the challenges that our wilderness faces in not only Tasmania, but the wider world…

The Vanishing World Indeed.

Deirdre Slattery’s review of the book This Vanishing Land can be see here.

Previous Post: Workshop: Introduction to Large Format Photography

Charles, an excellent review on the exhibition and the man. I was planning a trip to Tasmania next autumn, looks like I will bring that forward two or three weeks!

Thanks Murray, definitely worth the visit…!

Charles,

Thankyou very much for this substantial review of Olegas Truchanas’ significant and influential body of environmental photography of Tasmania’s south-west that were made in the late 1950s and 1960s into the early 1970s. This was at a time when there was a national ignorance of the untamed splendour of this natural landscape in Tasmania. Australians could only see the wild places through pictures.

There are affinities between Truchanas and Lake Pedder and Eliot Porter and Lake Powell (Utah) created in 1963 by the damming of Glen Canyon. The flooding of Lake Pedder and Glen Canyon have been interpreted as establishing much of the modern environmentalist movement in Australia (Australian Conservation Foundation) and the USA (Sierra Club).

As Porter wrote in his first book, In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World, “Photography is a strong tool, a propaganda device, and a weapon for the defence of the environment…and therefore, for the fostering of a healthy human race, and even very likely for its survival.”

Do you know if Olgas knew about Eliot Porter’s work?

Hi Gary,

I am not aware of the work of Eliot Porter in regards to Lake Powell, nor if Olegas knew of his work. That might be a question for someone that knew him personally. I would be interested to know more about the direct influences on Olegas though…