Folio: Murray White

Relationship in Landscape

Relationship consistently emerges as a theme across many photographic genres. Photojournalists capture images that define relationships, often with more clarity than the words that accompany them. Commercial photography entices us to consume goods with visual cues of personal fulfilment – happiness, it appears, is married to everything that can be eaten, worn, driven or touched…. Portrait and wedding photographers reveal character insights and family links as a priority function; aesthetics amount to little if Aunt Mabel isn’t standing next to her sisters!

Landscape photography on the other hand, is traditionally deemed devoid of relationship, and is typically defined only by its aesthetic. It is common for a landscape photograph to take us on a visual journey that reveals the nuances of light, the structure and detail of natural elements; perhaps even the implied emotional response of the photographer to its setting. At a deeper level we may feel a bond to a particular image by virtue of nostalgia, environmental empathy, or some other personal interpretation.

However as viewers we tend not to look for relationships associated with landscape, especially within untouched wilderness. In an intellectual sense this is entirely understandable, as any apparent connection can only exist as a random juxtaposition. Order and meaningful assembly will more likely be attributed to human intervention – those hedges, dry stone walls and cultivated gardens defined by blocks of untainted colour.

In recent years I have come to look at natural landscape through the eyes of a curious participant rather than just as an impartial observer. In my case this transition happened very quickly indeed, and was largely driven by the possibilities of B&W film photography. Having met a number of enthusiastic practitioners, I too became swept along by the infectious and considered methodology apparently intrinsic to this craft – especially, but not exclusively, behind the ground glass of a view camera.

There is no doubt in my mind that the restrictions inherent to film photography actually assist in fostering a rapport with landscape. For although a digital capture with exposure and focus stacking capabilities will almost certainly produce a clinically perfect image, there is something a little incongruous about allowing the science of technology to define the magic of beauty. By way of contrast, film users surrender just enough control and consistency to only share in the final creation, where the print is subject to more organic influences.

This nebulous relationship relies upon both photographer and viewer to consider landscape as a partner, rather than as a passive entity, merely existing for our use. I have travelled widely within Australia, but only now have come to realise that genuine depth of landscape emerges not from a perceived exotic aesthetic, but through fundamental visual signals. Our landscape is well able to speak, but first we must look for mutual links to begin to interpret its language.

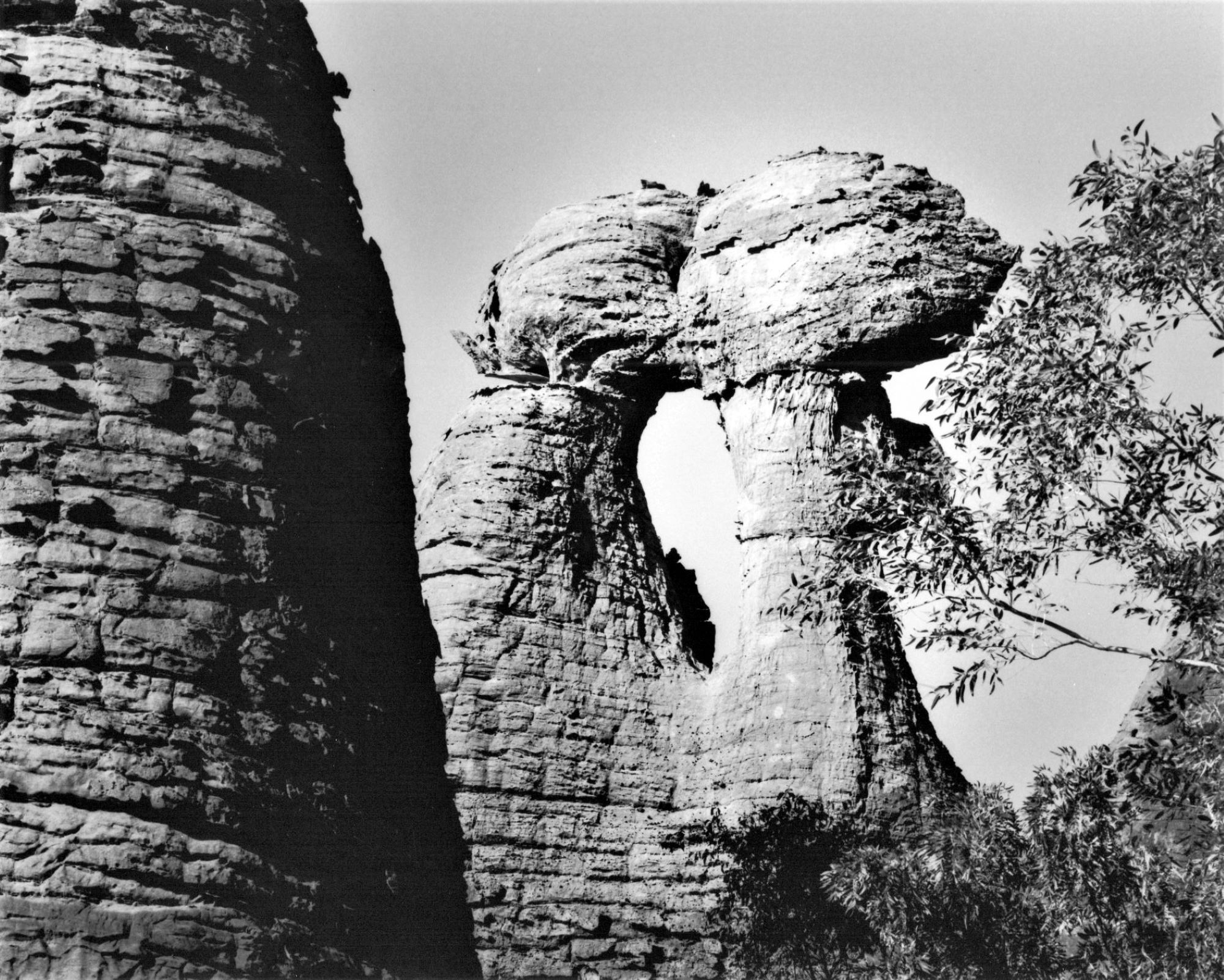

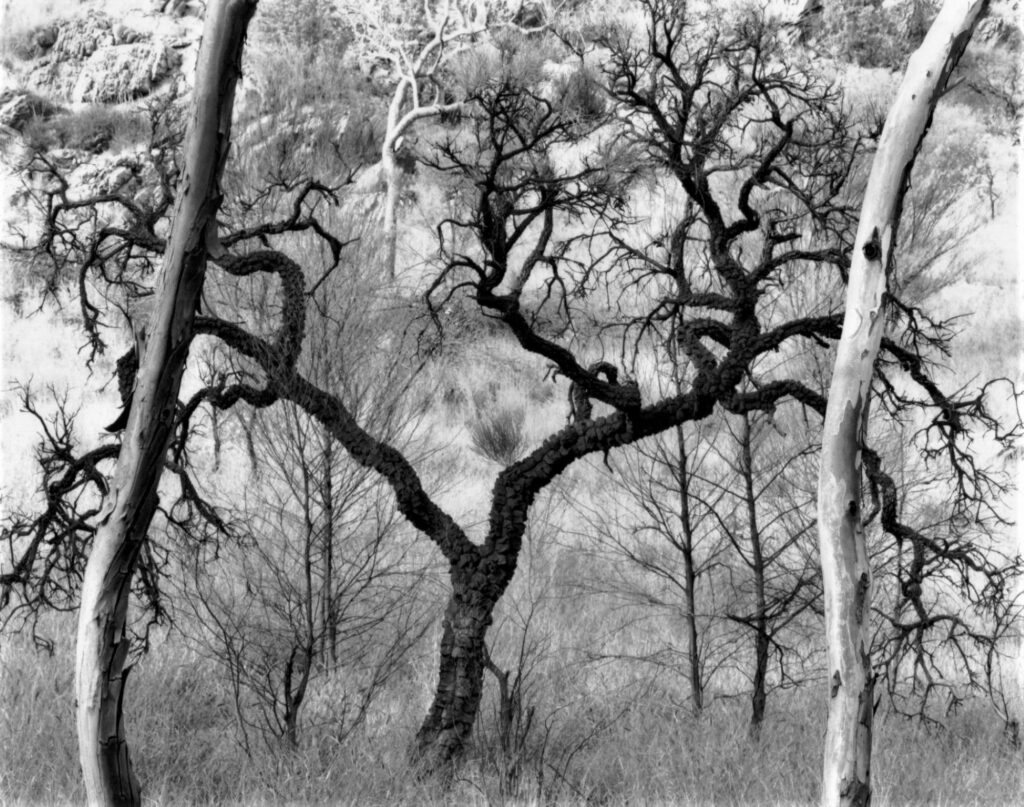

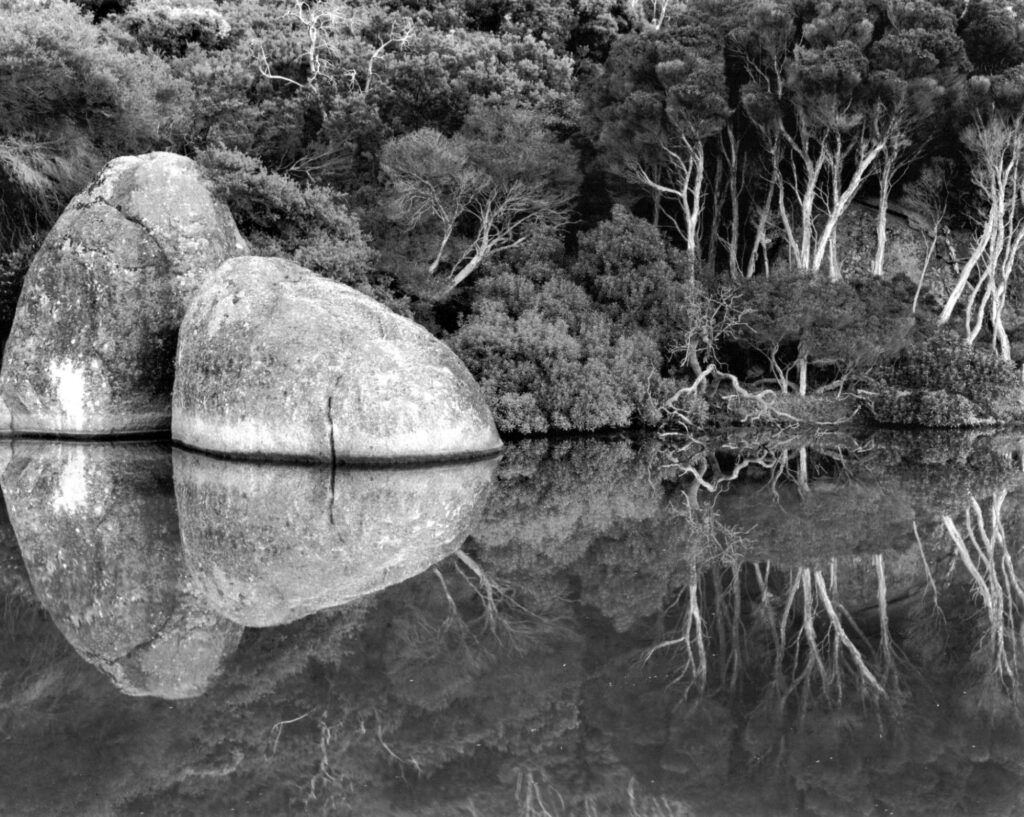

The images here attempt to share my vision of the natural world, using the concept of relationship to start the conversation. Images such as ‘The Kiss’, ‘The Mediator’ and ‘The Standoff’, use natural features as metaphors of human behaviour and interaction. ‘DNA’ expands on this theme with both commonality and diversity defining the same image. Are we looking at common structure disturbed by variation, or variation linked by a common structure?

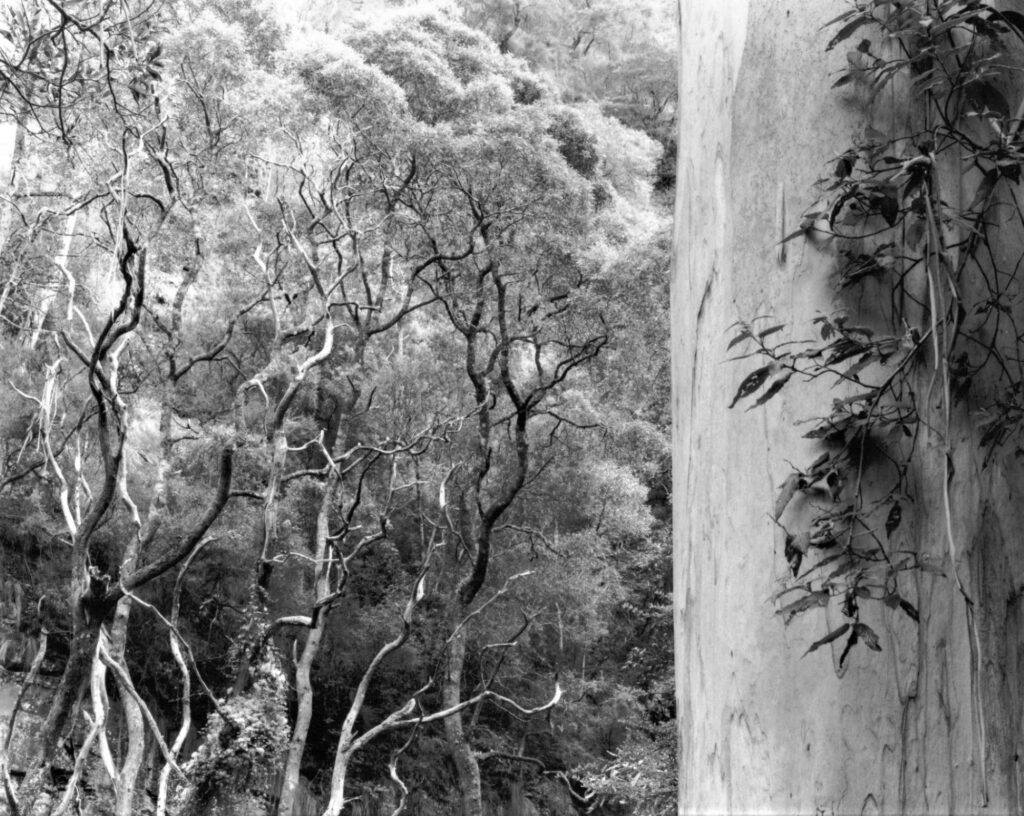

Group relationships such as ‘Fallen’ or ‘Can’t See Me’, imply activity within otherwise static elements. Branches extend like arms, with tree structures grouped to suggest conscious intent. A similar concept could define ‘Handshake’, as repetitions of line appear to merge.

Perhaps more conceptual is ‘Letting Go’ and the uneasy relationship between a dead tree and the reflection of living background foliage. In truth, neither element is directly related, but the juxtaposition may suggest otherwise. Equally suggestive to me is ‘Divine Faith’ – a kneeling rock structure seemingly confined between the forces of light and dark.

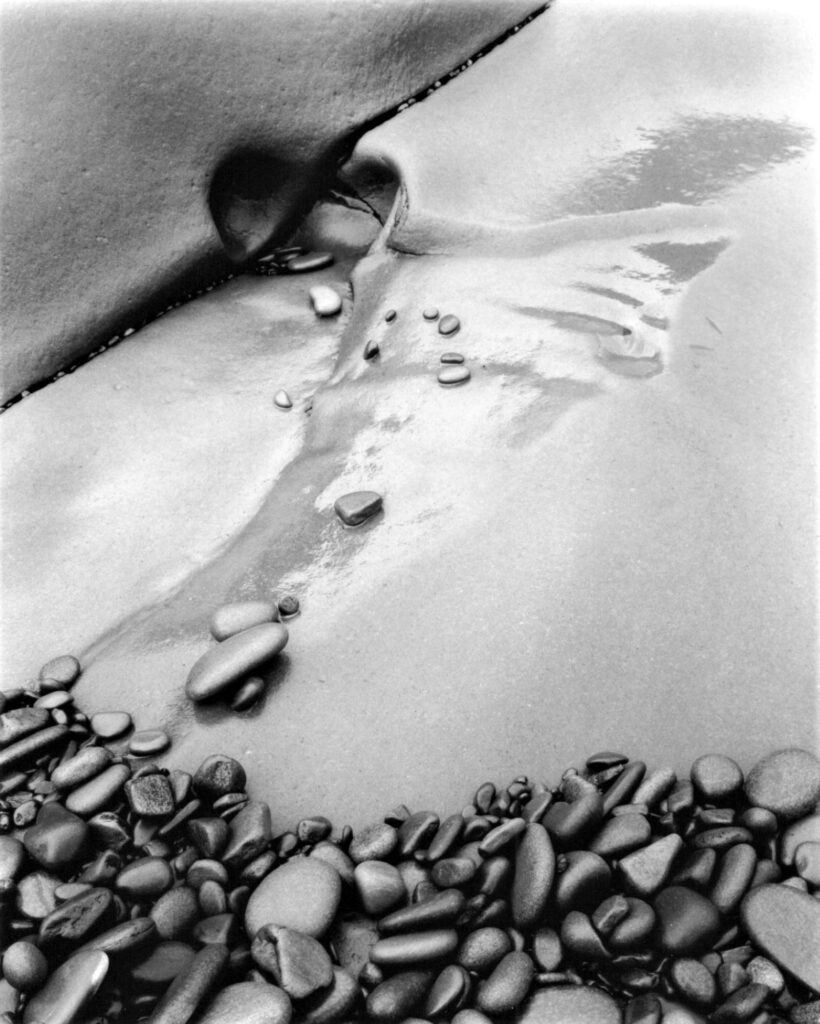

The polarised relationship between light and dark is also questioned in the somewhat alien, ‘Crucible of Life’. Another coastal scene, ‘Bonded at Birth’ is perhaps even more ambiguous, raising doubts as to the genesis of these pebbles, despite it being an exact portrayal of reality. (Well, as exact as one can portray reality through a standard lens, onto B&W film, and with the discriminating power of selection). It was important to me however, that none of these images be manipulated in a structural sense, precisely to maintain an authentic relationship with landscape.

Only ‘Intersection Ahead’ breaks this mould to some extent, as I have chosen to further imply movement by exhibiting an inverted image. Whether a decision such as this remains consistent with the concept of reality (as opposed to truth) is uncertain to me right now. The elements of this image are exactly what were there at the moment of exposure, and indeed, many of these compositions were conceptualised upside down on the ground glass of a view camera.

I guess that justifications can be made for all decisions – photographic or otherwise. However my starting point is that landscape deserves to be heard, and respected as a partner. We have a relationship with the natural world, and if photography can tune in to this connection, we should take the time to listen.

More of Murray’s work can be seen on his website and at his home gallery in regional Victoria as part of Southern Open Studios 2022 on 26th and 27th March 2022. More information can be seen here.

Murray’s essay My Black & White World can be seen here, and his The Photograph Considered can be seen here.

A very thoughtful insight into how you see.

Thankyou Shane, I too like to hear how others approach their photography, especially landscape photography!