View Camera Australia is proud to present Online Exhibition number…

Destination Kiama – part four – The Shoalhaven – Murray White

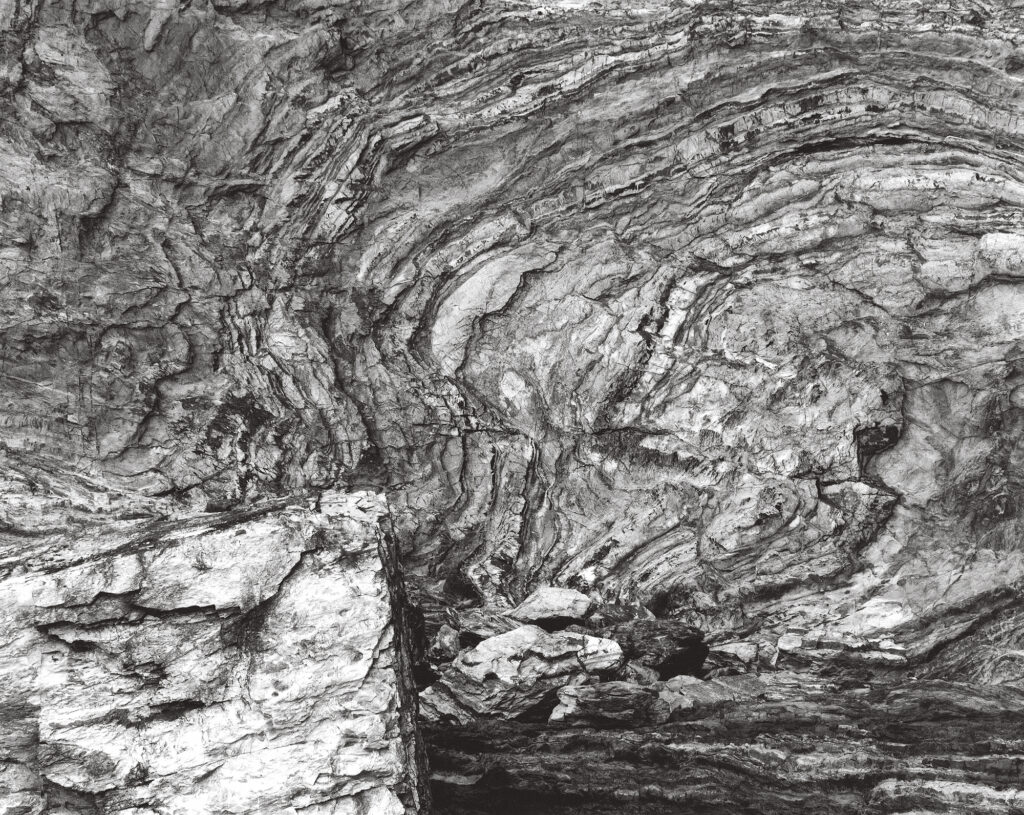

As we headed north from Batemans Bay on the last leg of our south coast amble, it became clear that the increasingly larger urban areas did not impact noticeably the scenic value of the remaining undeveloped land. Murramarong National Park for example protects some of the most diverse and captivating headland that we had the good fortune to visit; and in fact for me, this area was probably the single most remarkable and photographically rewarding destination of our trip.

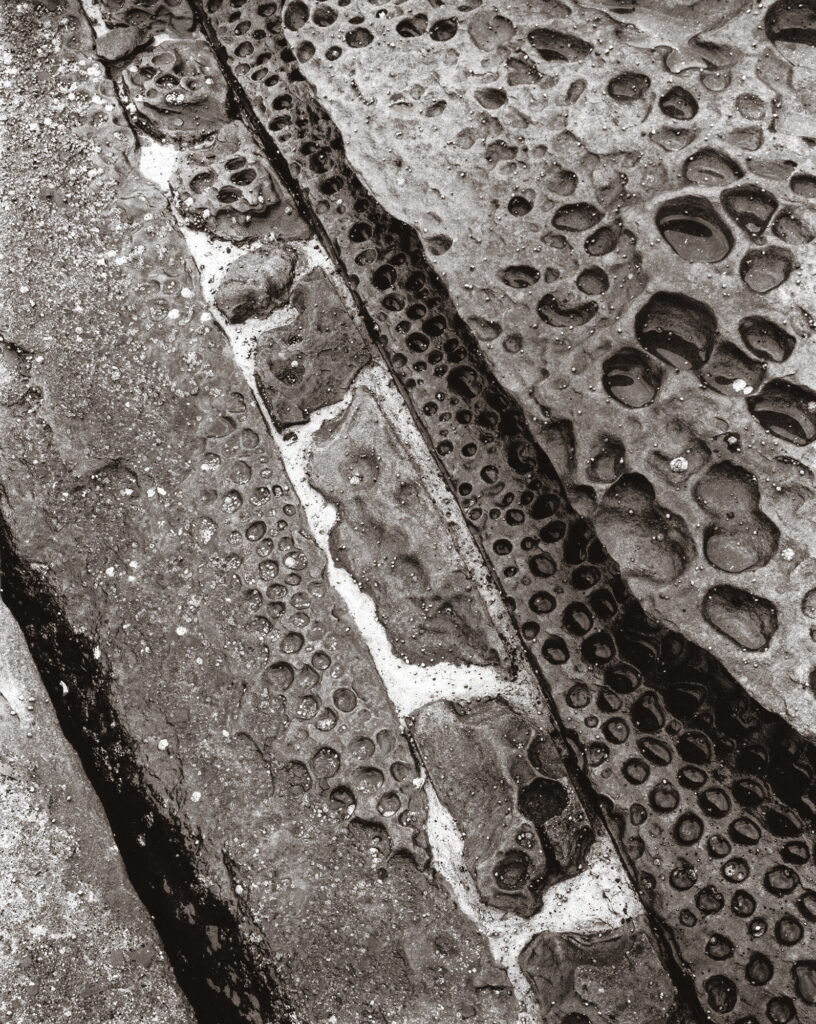

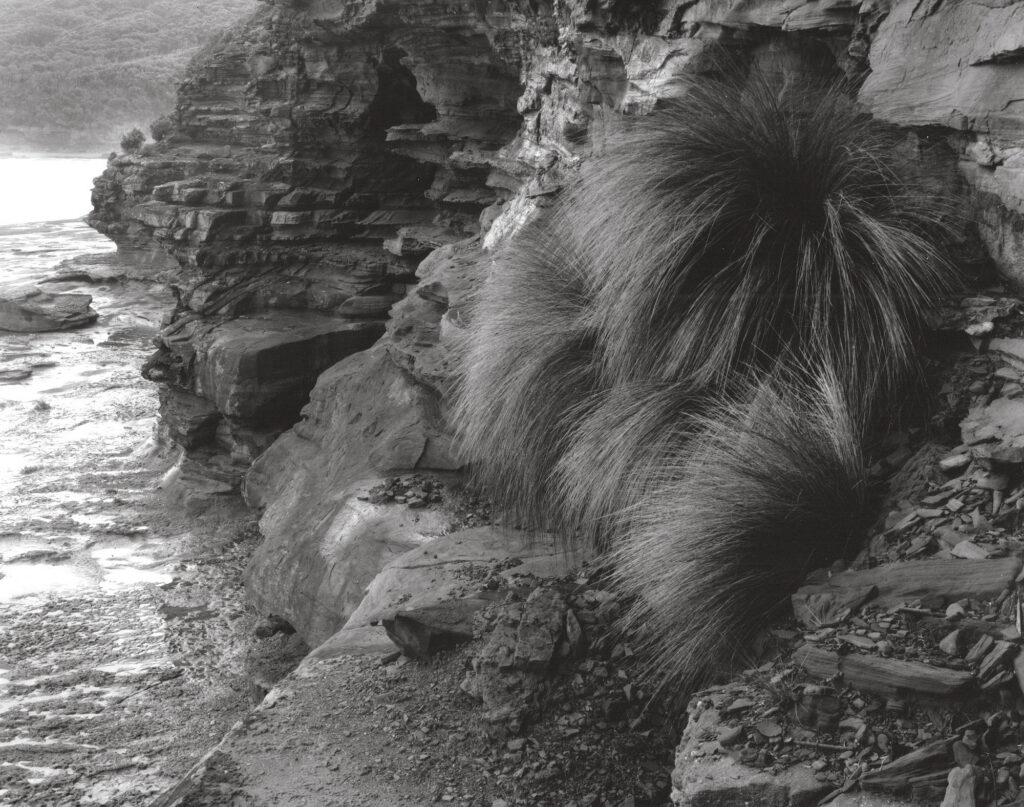

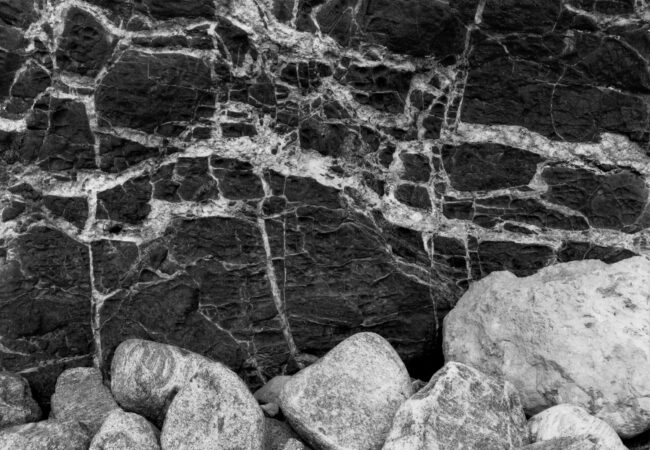

There are a number of camping possibilities along this section of coast, from the urbanised village strip at Durras to the quieter options at Pebbly Beach and North Head. We camped at Pretty Beach and North Head, to enjoy easy beach access and some amazing coastal rock formations. We were even pleasantly surprised to find a stand of beautiful mahogany gums around North Head campground, strangely contorted from their DNA lottery and ocean wind assault, but happily spared from the 2019/20 bushfires.

Walking tracks follow much of the coastline around here, although in some parts they head well inland to avoid eroded cliffs and impenetrable vegetation. Beach and open headland sections are a pleasure to visit, with typically informal pathways and a need to pick your own line over obstacles; a task often impacted by the tidal status. We chose to visit by vehicle the numerous access points at Murramarong, then walk what we could comfortably do in three or four hours. Given that our travels only scratched the surface of this national park, I can only assume from what we did see, that those intent on a more lengthy hike will be in for a real treat.

It is worth mentioning that NSW national park areas require an access permit, even for day usage. We purchased an annual pass prior to our trip, which we found to be well worthwhile as we visited many parks in our travels, but even for casual tourists the cost will pay for itself after just a handful of visits. National Park camping permits are also required for those staying overnight, and can be purchased online or over the phone, ideally prior to your actual visit. The system works reasonably well if you are able to plan an itinerary in advance, and its timing doesn’t clash with school holiday periods. We weren’t that organised but were still able to book all of the parks that we wished to camp in, even on the same day in some cases.

Booderee National Park in Jervis Bay Territory applies another access/camping arrangement, as it is not part of NSW. However the camping areas of Caves Beach, Green Patch and Bristol Point are very popular and will most likely need to be booked in advance. We stayed at Green Patch and enjoyed visiting a number of the area’s coastal features, together with the less than formal but nonetheless beautiful Botanic Gardens surrounding Lake McKenzie.

Our visit in early autumn was ideal for large format photography with mostly light winds and cloudy days. Winter would probably be an equally suitable season here to get under the dark cloth, but I would think that summer could be quite warm and almost certainly very busy. I know that my preference with a view camera in particular, is to avoid the more popular periods, and hopefully those activities that may impact our endeavours (although even on our off season trip I still managed to cross paths with an eBike rider doing some circle work in the fresh sand on his balloon tyres, apparently oblivious to the welfare of those early morning walkers around him).

From Jervis Bay we followed a contorted route around inlets and points to cross the Shoalhaven River at Nowra, before heading east again to Seven Mile Beach NP. There is no camping within this park but plenty of beach access points and picnic facilities for those visitors on a longer day trip. We ended up camping at Kiama that night, but there are several other options nearby.

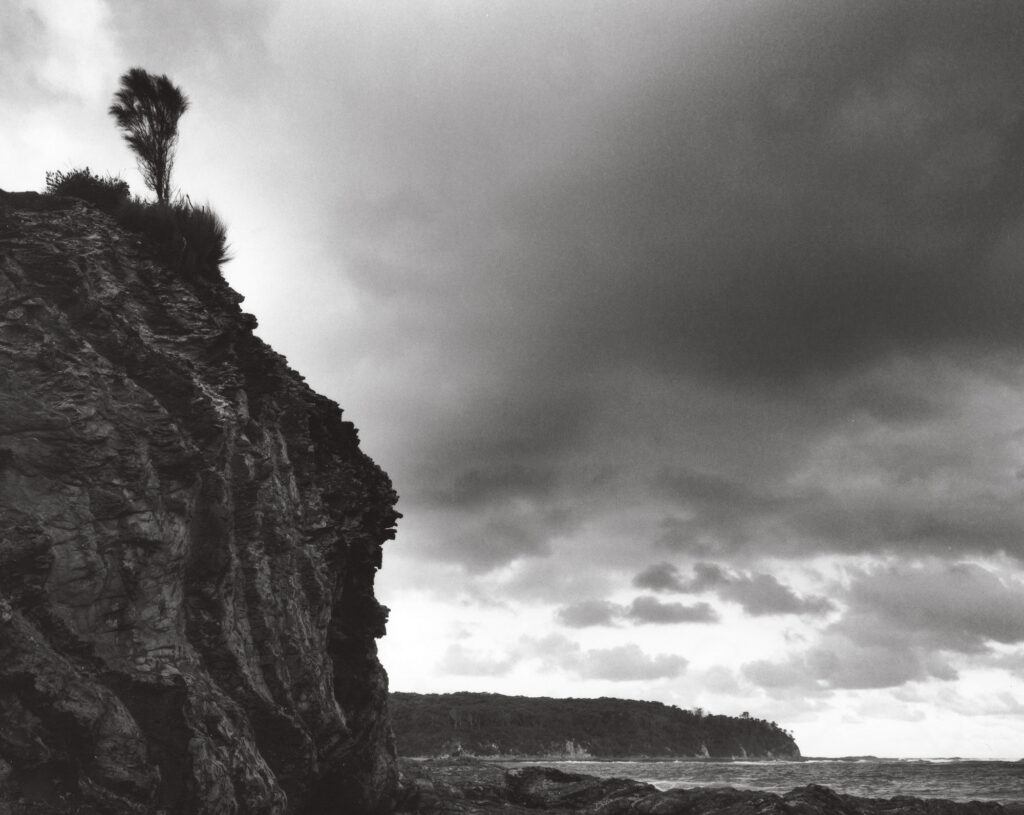

It was the rocky cliffs of Kiama that flagged the last strip of mostly low housing density coastline, and our return home. For me Kiama also brought into clearer focus some elements of my photographic practice that I had never really considered to any great extent before. One aspect that underpins all of my photographic decision making is a desire to only capture that part of Nature reflective of its own processes, or at least those views and aspects that don’t explicitly suggest of human influences.

Of course human impacts are part of Nature as we define it, and photographs that reveal of how our environment is responding to a force that has proven capable, and indeed insensitive of considerable change, are powerful corroborators. However I would like to look at the natural world, perhaps as it has been evolving for the overwhelming majority of its existence, when seismic, volcanic and weather related influences were the sole architects of its visual being. Now I admit that I cannot always recognise those impacts attributable to humankind, or identify introduced plants for example, but I try as much as possible to limit their presence in my images.

So for example Bombo Quarry near Kiama is for me a no go zone. Yes, the coastal spires and curious geological remnants of human endeavour are photogenic subjects, but I don’t wish to capture our landscape knowing that its aesthetic existence is directly attributable to actions not of a more ‘natural’ origin. Now without doubt a case could be made that cleared land regrowth, the damming of previously open valleys and countless other wilderness incursions are equally valid reasons and locations to apply that same visual standard, and in many cases I do. However my personal view is that in an environment where human impact is never far away, I can’t always avoid its influence but wish to at least minimise its visibility.

Another consideration for me that is less troubling in a definitional sense is the capture of well known subjects like Horsehead Rock near Bermagui or even The Blowholes here at Kiama. I chose to visit but not photograph these features, not because they are unworthy in an aesthetic sense (I think it unlikely that such declarations of a diverse natural world are even valid), but because it would be difficult to find a fresh interpretation of these subjects that have been so intensively photographed.

I guess the analogy could be made of Uluru for example, that yet another broad view will do nothing more than replicate what most of us already know. And despite that visual repetition, there will always be more people lined up to capture their version of this iconic subject, albeit a version that regardless of the inclusion of the individual photographer and their companions, will likely remain indistinguishable from the countless other captures made before.

Perhaps for many people, the process of landscape photography is not necessarily an investigative tool in their search for spirit of place, but rather affirmation that they too have been privy to the same experience as others. The photograph not only provides irrefutable evidence of the visit, but its implied message is one of a deeper understanding; one of actually having been there and exposed our every sense to its presence.

The inadequacy of this assessment is well illustrated by the tour buses at Uluru frantically ushering wide eyed tourists in the late afternoon light to Sunset Strip for their ‘experience’ of this clearly powerful subject, and a subsequent desire to capture that moment. The immediate presence of Uluru is even to repeat visitors quite overwhelming, but can we absorb its complexity with one eye firmly fixed on the clock? Now I make no judgement about anybody for their choice of itinerary or destination. We all play our cards as they are dealt, and even I recognise the irony of me having visited dozens of destinations in just as many days here on the south coast.

However I do think that view camera users (and analogue enthusiasts generally) are more likely to absorb themselves in the setting before turning to those subjects and visual identities reflective of it. Part of this familiarity process is without doubt the mechanics of a slower preparation for the moment, and the limitations of film that demand a more considered and sympathetic approach. But I wonder whether for us the photograph is more personal, the physical product of a lingering partnership between subject and our visual intent. Perhaps in the process of rendering our environment’s character, our emulsion captures just a little of our own. For me this journey has exposed just that.

Part three can be seen here.

Next Post: Folio: Alex Gard

A fantastic series Murray, I have enjoyed following along as they each part has been published. Thanks for sharing your thoughts and images… So many great works nestled here, and I have to say that the final image has to be my favourite. The visual drama of the motion captured in the water, juxtaposed with the rock and reflection, striking!

Thanks very much Charles, I too enjoy seeing what others are doing and how and why they approach analogue photography as they do. There are some fantastic subjects right along the NSW south coast, it was a pleasure to undertake the journey. Cheers, Murray