Pancro400 is a panchromatic film made up of two emulsions,…

Book Review: Traces – Chris Bell by Harry Nankin

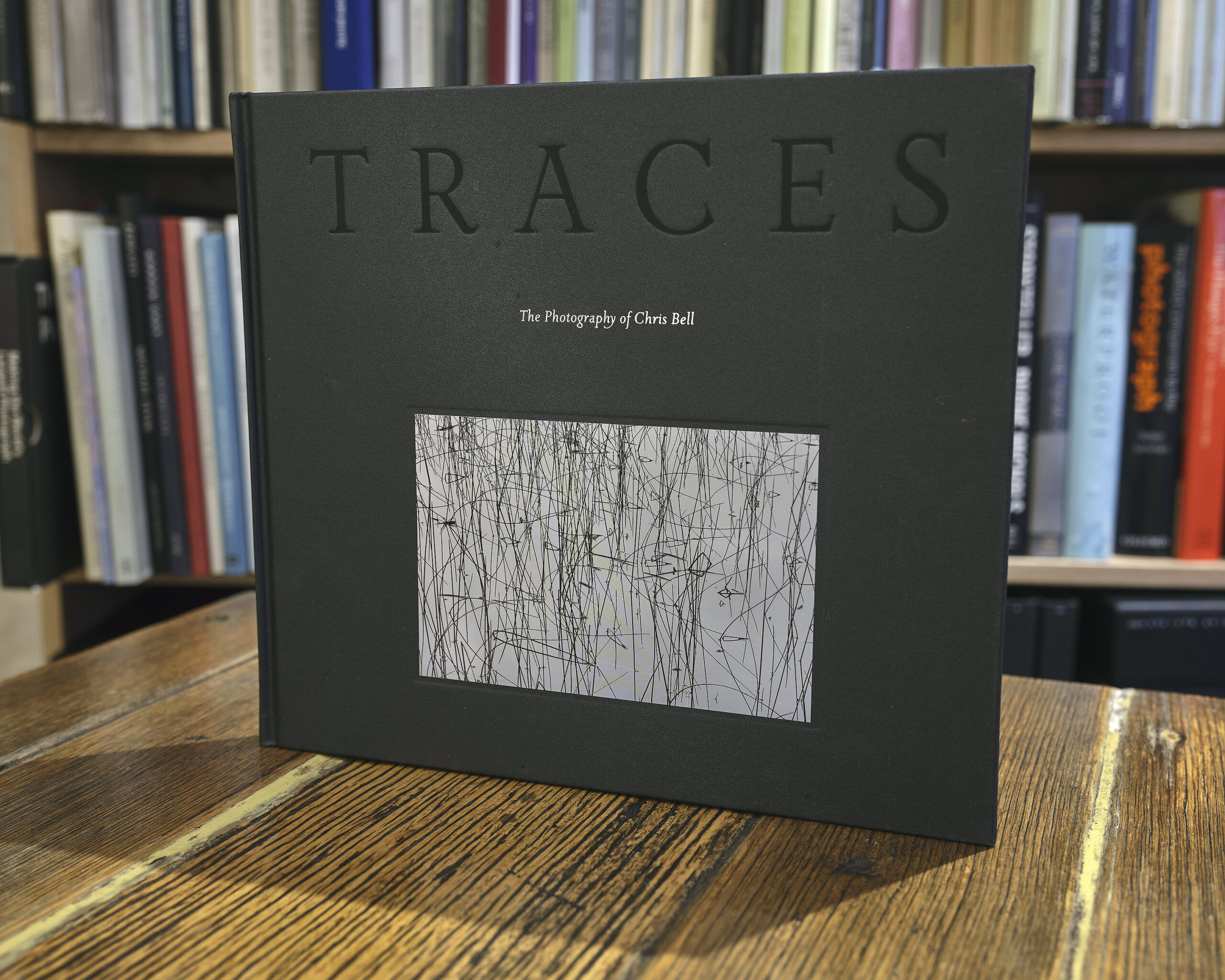

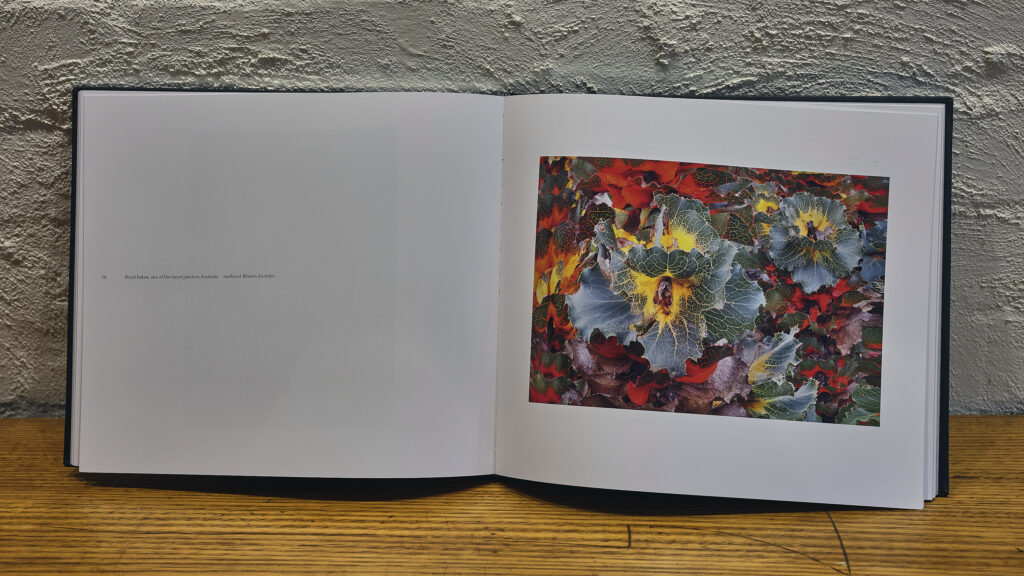

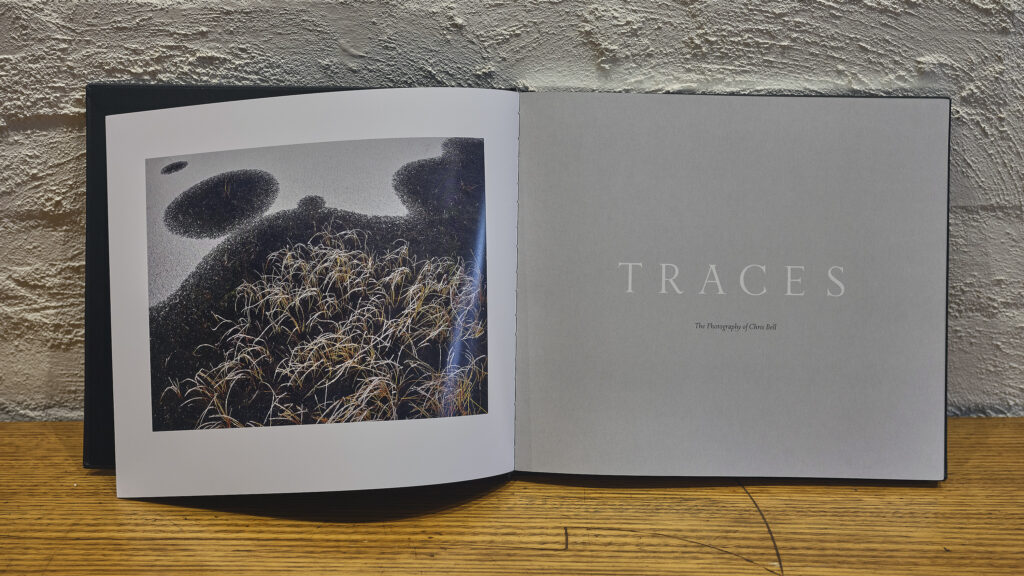

It’s hard to casually leaf through renowned Tasmanian landscape photographer Chris Bell’s latest book Traces. Rather, it’s a publication that needs to be savoured, slowly, page by page. And not just by our eyes. The embossed title and exquisite hero picture adhered to the grey cloth of the elegant large-format casebound cover and the heavy satiny paper stock carrying the pictures within are a delight to the touch, to trace with palm and fingers. Essays printed on lighter matt grey stock bookend the picture pages within. A Foreward by Jon Addison encapsulates what distinguishes this selection from much of Chris Bell’s previous published work as well as generic wilderness fare as a ‘focus on colour, shape, form and texture…rooted in the pallets and patterns of place’. Addison compares the books pictures to the modernist paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe. Yet such comparisons with painting seem superfluous when photography has its own glorious legitimating pedigree: in this instance pattern finders like Harry Callahan and Brett Weston (albeit mostly in monochrome) and, most pertinently, the colour studies pioneered by Eliot Porter he called ‘intimate landscapes’. Tim Bonyhady in his introductory essay describes this as focusing on ‘the small and often ephemeral’ explaining that such approaches ‘fall within a minority tradition in the celebration of what was once dubbed wilderness…As Chris Bell has shifted his focus to he has increasingly made abstract art. His seemingly simple pictures hold our gaze. They draw us back to look again’. Indeed.

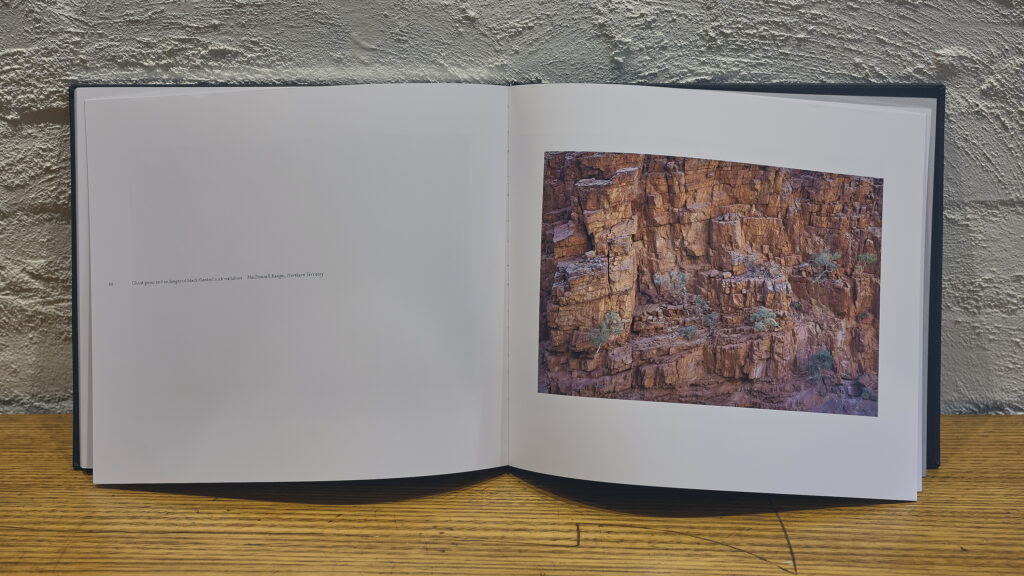

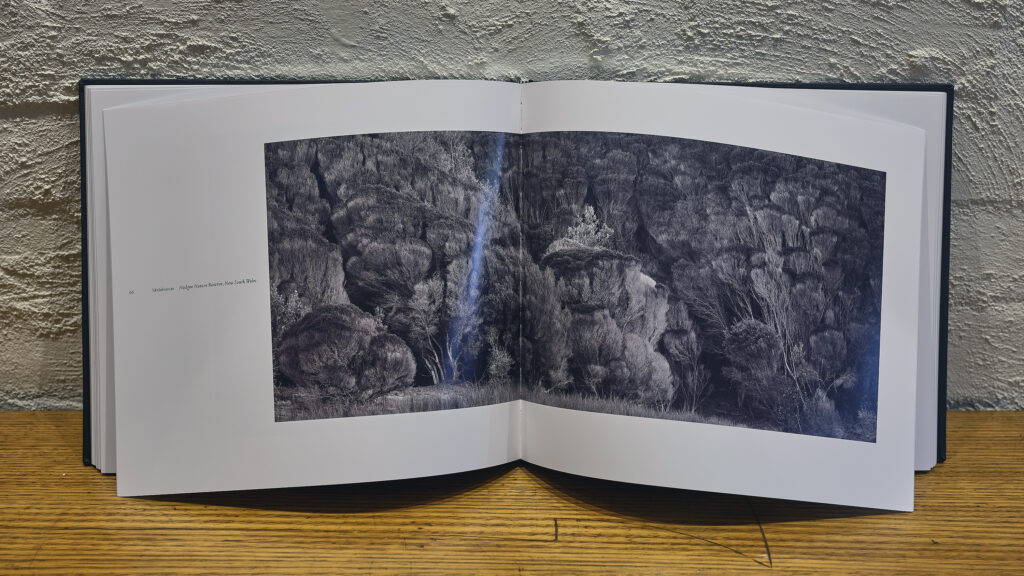

But the photographs are not all of a kind. It would be more accurate to describe Traces as a showcase of seven distinct photographic styles. The introductory set, one of which is also on the cover, are close-cropped views of reeds and their reflections some captioned as being in Wild Rivers National Park. They are visions of abstract perfection, ecologically of place but aesthetically other worldly, ’placeless’ as Bonyhady aptly observes: metaphors for what is bigger and more enduring than any of us. If these photographs have another visual mediums analogue at all it isn’t O’Keefe’s but Ukiyo-e: Japanese woodcuts. A second group are of horizonless seashores, lichen, ice and bare stone of ambiguous scale and shallow depth of field: sumptuous pigments, blobs, striations, fissures and whorls. Delights of form and colour. A third series are oblique colour fields of tidal and inland sand surfaces. Here, yes O’Keefe’s canvasses are a fit. A fourth are forest floor and insect nest close ups where we have a sense of scale and because of identifiable botany, a rough clue to locale. A fifth are oblique scenes of woodland floors, heathlands, alpine ice fields, water reflections, forest in snow, cliffs with insects, haze and shadows. Exemplary ‘intimate landscapes’. A sixth look like delightful interlopers. Among them is a ghostly vision of ‘old growth myrtle forest in mist’; the superb (what looks like but isn’t an aerial overview of a river delta) ‘underground stream terminus’ and the intriguing ‘Ghost gums and endangered black-flanked rock wallabies’. Hidden in its ochre cliffs the question is—to paraphrase a popular saying—‘where’s’ wallaby?’ You have to study it very closely. I think Chris Bell is smiling. Abutting the six groups of eye watering colour is a seventh: five black and white’s. One of ‘sand patterns on a remote beach’ in SW Tasmania is a drama where our attention is drawn to the silhouetted horizon and the stormy sky. The picture introduces the beachy colour close ups that follow. We aren’t told which if any of these were b&w capture or colour desaturated for effect.

Like the exhibition of prints in Launceston accompanying the books release, the layout is designed to isolate our attention on each picture’s specialness. With the exception of five impressive double page spreads, the photographs are presented singly on a right hand page, captioned to the left all surrounded by ample unmarked white paper negative space. And like almost every picture ever published made by Chris Bell every reproduction in this book is acutely perceived, meticulously composed, technically immaculate and finely positioned on the page.

But I have quibbles. I am for instance not entirely convinced any of the fifth and sixth sets of images (many of which are closer to traditional wilderness genre landscapes) belong in this volume. As individually superb photographs as most of them are, their relative readability feels inconsistent with the patterning, ambiguity and abstraction of most of the other images. And there’s the monochromes. The big difference between photographic colour and its absence is not mere verisimilitude. It’s eros and inference. Black and white demands greater interpretive reading, more attentive to form, tone and, above all, metaphor, than colour. Their chromatic muteness demands more of us whilst breaking up the lush page-after-page reverie of the colour. But maybe it’s just a question of taste.

If you only read the introductory words and peruse its wonderful pictures Traces is simply a celebration of nature. But if you also attend to its final lines (and read between them) the book takes on a different tone. In the Afterword Chris Bell tells his story. Of when young being ‘mesmerised’ by the ‘specialness’ of the wilds of Kanangra Walls in NSW, then directionless: ‘five wasted years in the armed services’ followed by ‘drifting aimlessly from one meaningless occupation to another’. Then, in another NSW wild place, ‘stream-side’, finding ‘the world of birds’ he turned to wildlife painting. Moving to Tasmania in 1972 at the height of the Lake Pedder campaign where ‘It was no longer just birds but the places they belonged to’ that attracted him. What he doesn’t write about is the patience, coping with the discomfort and the sheer physical effort—the stoic iron will—required to record the pictures in this and all his prior publications. Backpacking camping and imaging equipment (such as his weighty 4 x 5 inch format Linhof Tekinika field camera and tripod) deep into remote places to create images such as these year after year is no mean feat.

Chris Bell concludes he is conscious that many of the scenes and places in this book may very soon be not of the world that is but reminder’s of ‘the world that used to be…Irrespective how the world may terminate, I will always have the memory at least of these special places that have made me who I am.’ Traces is poignancy in pictures.

Traces by Chris Bell can be purchased here.

Next Post: Folio: James Niven