Mount Arapiles, photography, and the dark pastoral – Gary Sauer-Thompson. Part one

A key issue in contemporary photography is how can photography address climate change, given the convincing account by climate science with respect to the geological epoch of the Anthropocene. We now live in a world where non-human entries are more vast and powerful than we are: our reality is caught up in them, and they could well dislodge us from our commanding position over nature. This points towards a dark ecology that assumes an awareness of our ecological dependency, coupled with our realisation of how we have been re-shaping and damaging the planet’s ecological systems. If we are to really think the interconnectedness of all forms of life and all things, then hesitation, uncertainty, irony, and thoughtfulness need to be put back into ecological thinking.

If photography is to be relevant to this present, then what could an eco-orientated photography say? What kind of story could it visually narrate? Could such a photography create a cultural space within which very different kinds of knowledge and practice meet?

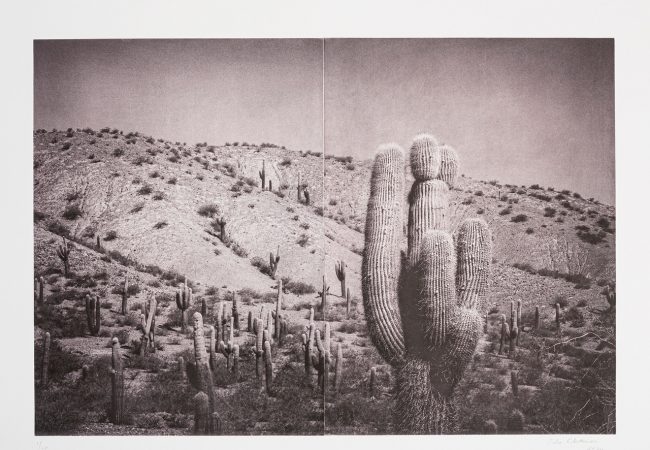

Though there is no blueprint, such a photography would need to be different to, and critical of, the photographic visions of settler colonial landscapes of John Watt Beattie and Nicholas Caire as these were premised on emptiness, pristine wilderness and pastoral utopias. It would also need to critically assess the aesthetic concepts established during the Romantic era, which framed the golden age of landscape painting and the visual arts in the nineteenth century. These aesthetic concepts divided the natural world into the 3 categories of the pastoral, the picturesque, and the the sublime. If the first two historically represented nature as a comforting source of physical and spiritual sustenance, the sublime referred to the thrill and danger of confronting untamed nature and its overwhelming forces, such as thunderstorms, alps, deep chasms, wild rivers and stormy seas.

Whilst both the pastoral and picturesque reference human kind’s ability to control the natural world, pastoral landscapes historically celebrated the dominion of humankind over nature. If the roots of the pastoral lie in a form of poetry that celebrates the pleasures and songs of the herdsmen, then this steadily expanded to a visual representation of rural nature that exhibits the ideas and sentiments of those to whom the country affords pleasures and employment. The scenes, which are usually peaceful, historically depicted ripe harvests, lovely gardens, manicured lawns with broad vistas and fattened livestock, were in contrast to the views of the court or the city. John Constable’s landscape paintings of the English countryside are a classic example.

In colonial Australia the settlers developed and tried to tame nature so that the land yielded the necessities the colonialists needed to live, as well as beauty and safety. If Joseph Lycett established the pastoral landscape tradition in Australia, then Arthur Streeton’s ‘The purple noon’s transparent might’ is an iconic example of the representation of the Australian pastoral landscape. In this tradition of the Australian idealisation of settler landscapes – Australia as a Promised Land – Europeans are seen to be in harmony with a fertile land; a land which has been ordered and produced by them, and in which they are able to experience leisure and pleasure. The Heidelberg School’s celebration of colour and light is a popular example of this tradition.

One problem with the colonial pastoral landscape as the middle ground between the city and wilderness is the masking and displacing of environmental destruction by nostalgic valuations of the very spaces and biosystems that were being destroyed. Another is that settler pastoralism historically denied and concealed the dispossession and the destruction of the First Nations people. Thirdly, the settler pastoral no longer makes sense in the Anthropocene, as it is an outmoded genre because the relation between the human and nonhuman worlds is no longer a harmonious one; it has become destructive. Both the Anthropocene being premised on the collapse of the human/nature divide and the current environmental crisis, in so far as it affects both the land and its inhabitants and the human and the more-than-human, challenges us to reconsider our conceptions of nature. To be contemporary an ecologically orientated photography and philosophy need to be critical of the pastoral tradition and no longer be nice and green and a celebration of all things natural.

If the aesthetic categories of the pastoral and picturesque are rejected then we are left with the Romantic sublime. In Australian photographic culture this has been developed by Bill Henson. Henson is an important figure because unlike many photographers who hold aesthetics in low esteem Henson does not have a fear of aesthetics; does not think that its time is well and truely over; nor does he reduce aesthetics to beauty then dismiss it wholesale. He accepts the core of the Romantic revolution, namely the institution of art as ontological knowledge and that art is an object of philosophy. The celebrated style of Bill Henson’s landscapes, which were shown in an exhibition in the Castlemaine Art Gallery in 2016, work within and develop, the tradition of the Romantic sublime in Australian as dreamscapes.

An accessible and useful interpretation of the Romantic aesthetic background in the art institution is given by M. H. Abrams in The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition (1953). Abrams uses two metaphors to characterize the 18th and 19th-century English literature, respectively: the mirror as a cool, intellectual reflection of outward reality and the lamp as an illumination shed by artists upon their inner and outer worlds. The shift of emphasis from the former to the latter he takes to be the decisive event in the Romantic theory of knowledge as it emerged around the beginning of the nineteenth century. The artwork ceases to function as a mirror reflecting some external reality and becomes a lamp which projects its own internally generated light onto things. The underlying concept for the lamp is expression.

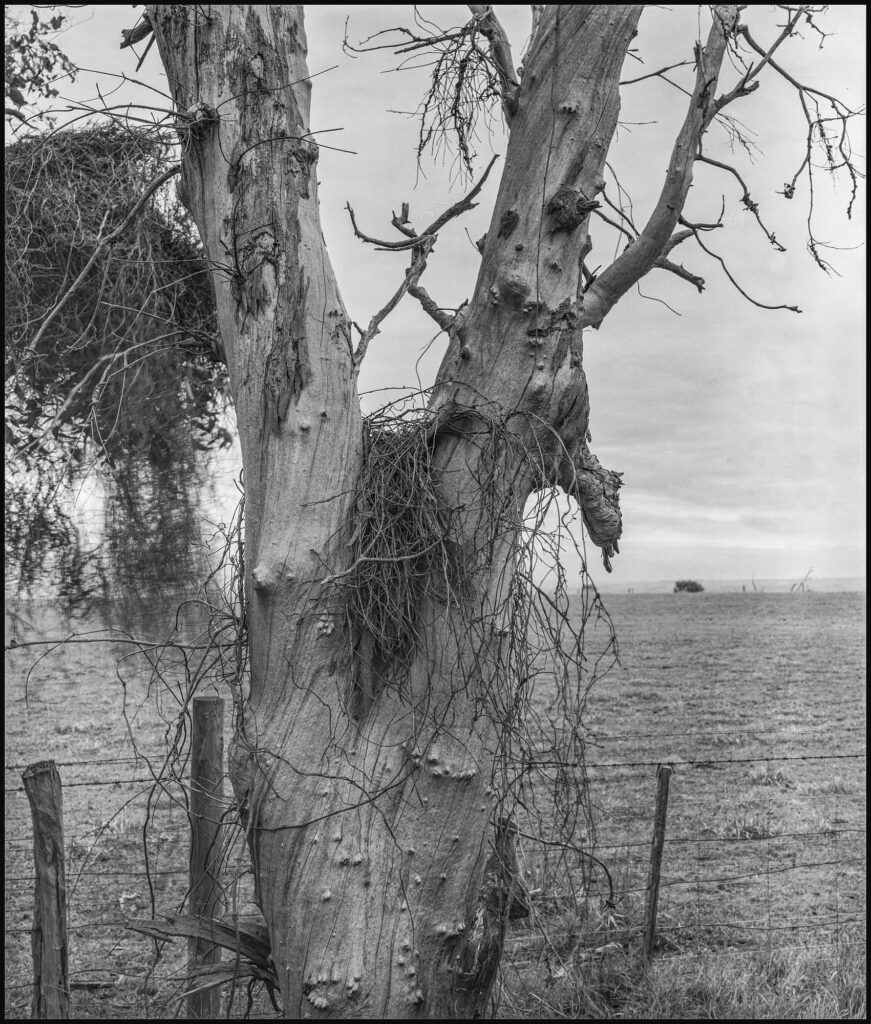

The mirror lamp duality is entrenched in Australia and if it situates Henson’s landscapes as developing the Romantic tradition, then it places nineteenth century photographers such as Captain Samuel Sweet in Adelaide in the mirror tradition. Though my large format photographic approach to the landscape would be situated within the mirror tradition, the the mirror metaphor doesn’t make sense of the way I approach my photography. This involves checking things out, thinking critically about the subject, and making judgements about how to photograph. My large format photography at Mt Arapiles-Tooan State Park in the Wimmera Plains in Victoria illustrates this approach.

Part two of this article will be published shortly.

Reference: Jarrod Hore, Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism, University of California Press, Oakland, 2022