I don’t like to crop my negatives; in fact…

Straight to Eight: Starting Large Format with the Horseman 810L

There’s a particular kind of silence that settles over a scene when you’re shooting 8×10. It’s not just the absence of a shutter curtain woosh or a mirror slap — it’s the absence of rush. Of distraction. Of second-guessing.

This article isn’t about technical specs, lab results, or vintage camera evangelism. It’s about diving headfirst into 8×10 as a working photographer—not because I had to, but because it was the logical next step for me. It’s for anyone standing on the edge of large format, wondering if they’re ready, or if they need to start with a “smaller” large format.

Spoiler: you don’t.

So You’re Thinking About Large Format

At a certain point, film photography becomes less about gear and more about intention. You slow down. You start noticing the space between frames. And before long, large format isn’t just a curiosity—it feels like the natural next step. Well, that, and the realisation that juggling three cameras on a hike “just in case” might be getting a bit out of hand.

For me, it wasn’t a whisper. It was more like a dare: What if you skipped 4×5 and went straight to 8×10?

I’ve returned to shooting film over the last decade, though in truth, it never felt like a departure—just a pause while the world went digital. Like many who came up during that transitional era, analogue wasn’t a novelty—it was simply what cameras did. My first photographs were taken on a crusty Kodak Instamatic 133 given to me by my nan. The shutter button was tentative, the flash non-existent—and I was hooked. In the early years, I shot on my dad’s old 35mm cameras before moving into digital point-and-shoots and DSLRs as technology took over. Digital quickly became the obvious choice for professional work: fast, convenient, efficient. But when it came to personal projects, I kept coming back to film. There’s something about its tactile, deliberate nature that digital can’t replicate—a sense that the images I care most about deserve to be made this way.

I’d been shooting 645 for a while, but eventually it started to feel like it wasn’t giving me quite enough. I wanted more from the negative—more detail, more presence. That’s what led me to the Mamiya Universal Press and Super 23. They gave me a 6×9 negatives, some movements, and a more deliberate way of working—all without giving up the flexibility I still needed in the field.

The Gateway Drug: Mamiya Super 23

If you haven’t used one, the Super 23 is a strange and wonderful beast. A medium format, rangefinder press camera with helicord focusing lenses, and a bellows-mounted rear standard, interchangeable backs (including 6×9 roll film and even an optional ground glass viewer), and the sort of rugged, industrial charm that makes it feel just as at home in a studio as it does stuffed into a backpack. With movements on the rear standard and a focusing mechanism that encourages deliberate composition, it’s basically a more convenient view camera—if your idea of convenience includes a camera the size of a mini sandwich toaster.

It was with the Super 23 that I began experimenting with movements, shallow depth of field, and the whole-body choreography of slow photography. And it got me thinking: if this is already how I like to shoot, why take a lateral step to 4×5?

Buying a 4×5 felt, frankly, redundant. The Super 23 already scratched many of those same itches—but with greater convenience, cheaper film, and fewer moving parts. What I didn’t have was the scale and presence of 8×10. I didn’t have those enormous negatives, the tonal range, the precision. If I was going to learn a new system, I wanted it to unlock something different—not just more of the same.

Why 8×10 (and Why Not 4×5?)

The sensible route is to start with 4×5. Learn your movements, get used to ground glass, deal with only moderately terrifying dark slides, and ease yourself into the rituals of large format with minimal cost and weight.

But the Mamiya had already taught me the rituals. I wanted the scale.

I chose 8×10 not despite its size, but because of it. If I was going to rewire part of my process, I may as well do it in a format that demanded my full attention. The sheer surface area of an 8×10 negative brings with it a level of intimacy and immersion that no other format had ever offered. You don’t snap an 8×10 photo. You negotiate with it. You listen. You compose, hesitate, refine. It’s portraiture as conversation. Landscape as meditation.

And, if I’m honest, I liked the absurdity of it. If I was going to carry a large format camera, it wasn’t going to be the compromise version.

It was going to be the whole damn horse.

Why the Horseman 810L?

When you start looking at 8×10 cameras, you quickly realise there’s no such thing as the “perfect” option—only trade-offs. Field cameras are lighter but often limited in movements. Studio monorails offer precision and flexibility, but they’re not exactly known for their portability.

The Horseman 810L is a monorail camera with zero pretence and a lot of presence.

This camera is a tool. Purpose-built. Precise. Reassuringly engineered. It doesn’t try to charm you with wood or brass—it just performs. Every geared movement is smooth and deliberate. The standards lock down with confidence. The rail glides. Once it’s set up, the whole system feels like it was designed to outlive us all.

It’s industrial, yes—but in the best possible way. Not crude. Not clunky. Just well-machined and unapologetically focused on function. It never feels fragile, and it doesn’t overcomplicate anything. It’s a system that rewards familiarity—something I’ve come to value more than elegance.

While it’s not exactly lightweight, the Horseman is surprisingly manageable. Carrying it on short hikes isn’t a deal breaker, and shooting outdoor portraits in backyards or working in makeshift home studios fits comfortably within its practical use. It’s a solid, reliable tool that simply gets the job done.

Building the Kit: Lenses, Holders, and the Rest

Buying the camera is only half the fun (and by fun, I mean the kind that involves lots of research, a few dead eBay links, and several late-night existential lens debates).

For lenses, I didn’t want to go full vintage. I wanted the familiarity of something modern, sharp, and coated—something that wouldn’t make me fight for contrast on a bright day, and that would complement the lenses I shoot with on my medium format camers. The Fujinon W 300mm f/5.6 ticked all the right boxes. Clean rendering, plenty of coverage, and it takes the same 77mm filters I already had in my kit. Familiarity is underrated when you’re stepping up formats.

Film holders? Just the one. It might raise a few eyebrows, but honestly, it’s enough for how I’m working right now. I’m developing with trays in my makeshift darkroom/bathroom, so a dozen holders and a Jobo system feel like overkill and a cost I’m not prepared to make. I’m not opposed to scaling up eventually—those Zebra developing systems that just hit kickstarter look like a nice future compromise—but for now, one holder and a rhythm of loading, shooting, and processing keeps things simple and focused.

The tripod? Already had one. The spec sheet said it could handle 20kg, which sounded like more than enough for the 10kg-ish load of the camera, lens, and holder. And to its credit, it’s been holding up—mostly. But it’s becoming clear that if I’m going to take this setup into more demanding outdoor environments for serious landscape work, the head’s going to need an upgrade. It’s fine for now, but let’s just say: confidence and stability aren’t always the same thing.

Other supporting gear rounds it out: a loupe for critical focus, a decent dark cloth (read: not a tea towel), and a reliable light meter. None of it’s exotic. All of it matters.

Putting the kit together hasn’t been about chasing perfection—it’s about building something that suits how I like to work. I didn’t need everything at once. I still don’t. It’s a process, and each piece earns its place through use. One camera, one lens, one holder—and a bit of patience—has been more than enough to start.

Learning the System

Coming to 8×10 as someone with a decade of film experience, nothing felt particularly foreign—just bigger, slower, and stripped of distraction. There’s a simplicity to large format that’s oddly comforting. No menus. No automation. Just lens, film, and light. If you understand the fundamentals of photography, large format doesn’t complicate them—it clarifies them.

Movements, for instance, weren’t a revelation—they were a refinement. The Super 23 had already trained me to think in planes, in tilts and swings. The Horseman just gave me more room to work. Using swing to draw out depth across a subject, or a touch of rear tilt to correct perspective in landscape work—it all felt like applying knowledge I’d already earned, just with a more precise brush.

Film handling was also less of a leap than people make it out to be. If you’ve ever loaded 35mm or medium format onto a spool in a change bag for home developing, you already have the muscle memory for working blind. Sheet film is just a different shape. Slide it in carefully, feel for the click of the notches, seat the dark slide—and you’re done. It’s not mystical. It’s just another routine that becomes second nature with a few repetitions.

Of course, large format requires a level of attention that’s simply not negotiable. There are no alarms or interlocks—just you, the process, and your ability to stay focused. It’s not that I made mistakes while venturing into this new way of picture making; it’s that I became aware of where mistakes could happen. A slightly misaligned bellows attachment, a film holder not seated fully, a shutter not closed before removing the dark slide—none of these are complicated issues, but they ask for care. So I take my time. I double-check. Not out of anxiety, but out of respect for the process. It’s a slower rhythm, but it’s clean. And it becomes a habit remarkably fast.

What surprised me most wasn’t how different it felt—but how natural. Large format strips photography back to its essentials. One image at a time. No buffer. No burst. Just you, the scene, and the light. No complication, just clarity.

How It Fits in My Broader Practice

Adding 8×10 to my workflow wasn’t about novelty—it was about intention. I didn’t need another camera. I needed a reason to make fewer photographs, more deliberately.

My broader practice has always orbited around observation. Human traces in geography. Emotions embedded in spaces. The quiet gestures of portraiture. I’ve worked across formats for years—35mm for speed and general impressions, a way to move fluidly and respond instinctively to what’s unfolding. Medium format offered more intimacy and control; it let me slow the frame just enough to compose with intention, while still staying connected to the moment. But 8×10 brought something different altogether—a kind of presence that made each photograph feel singular. Not one of many. One of one.

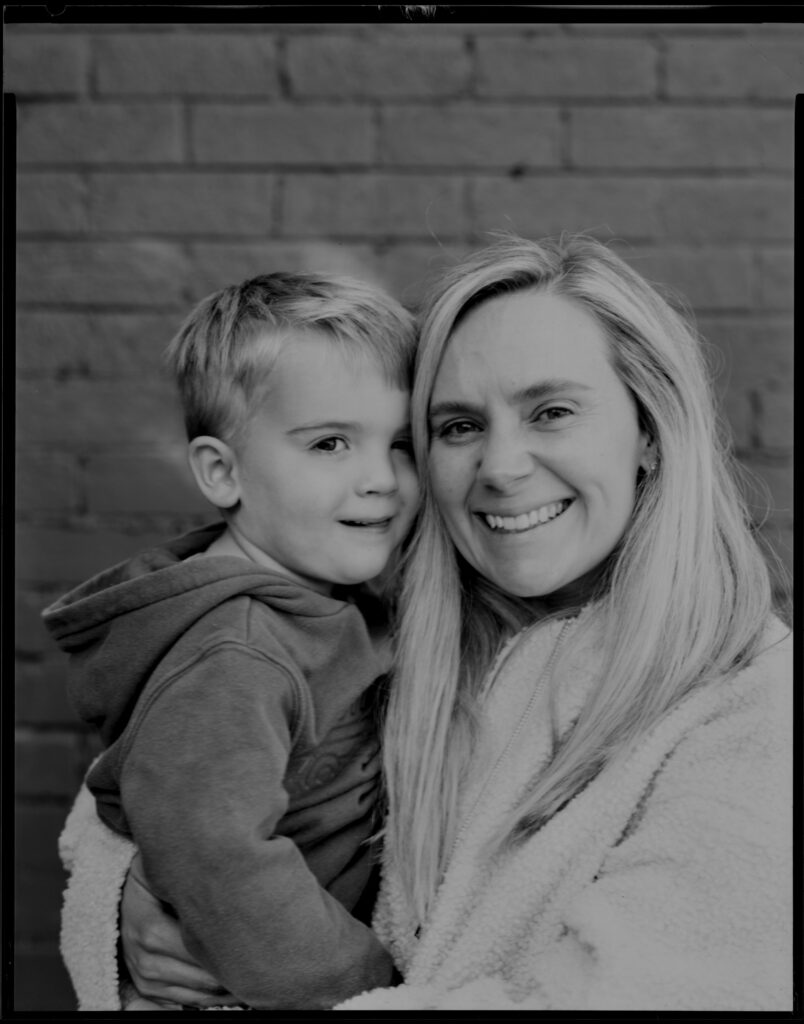

Where 35mm excels at flow, and medium format strikes a balance between detail and spontaneity, 8×10 is something else entirely: an anchor. It grounds an image within a wider body of work. It gives weight—literally and conceptually—to what I’m trying to explore. Whether I’m photographing a person or a place, the process forces a level of attention that shapes the subject itself. People hold themselves differently in front of a camera that takes five minutes to prepare. Landscapes shift as the light evolves while I compose. I’m not just capturing a moment—I’m inside it, shaping it alongside everything else.

And unlike faster systems, where you can shoot a dozen frames and sift through later, 8×10 asks you to mean it. There’s no machine-gunning the shutter or hoping something lands in editing. There’s just a scene, a decision, and a sheet of film. That kind of discipline doesn’t limit creativity—it sharpens it.

It also complements the rest of my gear. I still use smaller formats for exploratory work, sketching ideas, shooting on the fly. But when a concept starts to crystallise—when it deserves patience—I know the Horseman is the right tool. It’s become a kind of final draft camera. The one I’ll reach for when everything else has led me to a clear visual statement.

In that way, 8×10 hasn’t just influenced my process. It’s influenced my thinking. It reminded me that not everything needs to move quickly. That not every shot needs to be efficient. Sometimes the image asks for more time. And now, I have a camera that lets me give it.

Parting Thoughts: Encouragement for Beginners

There’s a kind of mythology around large format—particularly 8×10—that paints it as the domain of purists, technicians, or people with suspiciously strong lower backs. But the truth is: it’s just another tool. A beautiful one, yes. Demanding in all the right ways. But not exclusive. Not unreachable.

If you’re already comfortable with photography—if you understand exposure, composition, light—then 8×10 isn’t a leap into the unknown. It’s a return to the basics, just rendered at scale. It’s photography with the training wheels off.

There’s a lot of noise out there about needing to “start small.” Learn on 4×5. Make mistakes where they’re cheaper. But that’s not the only way. If 8×10 speaks to you—if you’re curious about the format, or just want to slow your process down and see your images contact-printed one-to-one the size of your head—then there’s no reason not to go straight in.

Yes, it costs more per shot. Yes, it’s heavier. But it also teaches you quickly. It rewards attention. And it brings with it a sense of purpose that smaller formats don’t always require. You won’t be making hundreds of images. But the ones you do make? They’ll matter—because you’ll have meant them to.

Start with whatever camera you can get your hands on. Borrow a camera. Buy second-hand like I did. Learn to load film in the dark. Carry a loupe. Embrace the tripod. Make peace with your shadow on the ground glass. And don’t wait to be “ready”—you won’t know what that means until you start.

8×10 isn’t intimidating once you’ve used it. It won’t replace all the other cameras in your kit—but it leaves a mark on how you see everything else.

Kade Beau Anderson is a Melbourne-based photographic artist whose practice centres on analogue and large format photography to explore themes of national identity, memory, and emotional states. Drawing on over a decade of experience as a content marketing specialist across higher education, global B2B, and the creative industries, Kade brings a strategic and narrative-driven approach to visual storytelling. His work often examines the quiet tensions of individuality through surreal and documentary modes. With a background in both science and communication, his practice reflects a deep engagement with place, process, and the craft of image-making.

Next Post: Exhibition: Man Ray & Max Dupain

Previous Post: The Photograph Considered number fifty two – Ian Raabe

A very interesting article Kade, I find it useful to understand how film photographers see the world, and what drives their particular vision. I’m interested whether you will use the 8X10 for silver gelatin contact prints or you intend to look at some alternative processes?

Hi Murry,

Thanks for the feedback, actually down the line I’ll be looking at drum scanning and printing large when images from the 8×10 fit into a larger body of work. I’m still making most of my projects across medium format – and I work in a hybrid method there. Scan and digital C-type prints or giclée depending on the subject matter.

I’m definitely looking into alternative processes with contact printing of 8×10, especially toned cyanotypes and Orotones using liquid emulsion on glass plates. I’d be keen to get hold of a contact printing frame if anyone has one lying around looking for a new home 🙂

But generally darkroom printing doesn’t fit into my current practice and workflow.