The Gate at Pentridge. Silver gelatin print. Walking through former Pentridge…

Darkroom – Craig Watson – part one

My life in darkrooms by Craig Watson part one.

My life in darkrooms began as a student in 1980 and my excitement in working in the darkroom remains as much today as when I saw my first print come to life in the developer all those years ago.

Much of my professional working life has been in darkrooms and I used my experiences from them all to create Focal Point Darkroom in North Geelong. Sadly, that darkroom no longer exists, but its legacy remains, in a small way, in my new darkroom in Geelong.

In 1980 I was studying Graphic Design at Swinburne Tech (now Swinburne University) in Melbourne’s Eastern suburbs. One subject was photography and our lecturer was former head of the Photographic Department at the Australian Antarctic Division, Allan Campbell-Drury. He was an inspiration, and his interest in the darkroom had a profound effect on me.

Graphic Design wasn’t my thing and I left Swinburne for a sales job at Ted’s Camera Stores in Melbourne. I didn’t know then what I wanted to do for my career, but knew it would involve photography. After six years at Ted’s and other camera stores, I began studying photography part-time at RMIT in Melbourne.

I rekindled my love of the darkroom and spent every available hour honing my printing skills. I was offered a part-time job, two days a week, at Leader Newspapers in Blackburn, photographing cars at used car dealerships for the Classifieds sections of a stable of suburban papers. It was a mundane job, but a great learning experience.

Those were still the days of wet processing 35mm black-and-white film and hand-printing in the darkroom. Shooting up to 300 cars, which needed to be on the editor’s desk by 5pm on the second day, taught me two important lessons. The first was how to ensure my camera exposures were spot-on first time, every time, as I could only spend a few seconds on each car. The other lesson was how to print quickly and accurately from those negs.

For anyone who has never worked in the hurly burly of a newspaper darkroom, especially when there is a big news story breaking, it is hard to imagine the flurry of activity that went on, even in a suburban newspaper, where everything is wanted an hour ago.

Learning to read negatives quickly, checking focus, composition, contrast and density, became an important skill. I would expose each negative of a film onto a sheet of 3½” x 5” RC paper, putting each sheet aside, numbering the backs as I went. I would then throw all 36 (give or take) prints into the developer, which was in a large stainless-steel tray, swishing them around as they developed, pulling them out as they reached the desired density and throwing them all straight into the fixer, in another large stainless tray.

Then I would move onto the next roll of film, exposing all the negatives onto another batch of paper. I would then pick out all the prints from the fixer and throw them into the very large stainless wash tank, which had continuously-circulating water, before putting the next batch of prints into the developer. This was all done with bare hands. No tongs or gloves. A quick rinse and dry of the hands was all that was needed to make sure fixer didn’t get on the undeveloped prints.

After the last batch of prints was in the fixer, I would start cleaning up my work bench before transferring the last lot of prints to the wash tank. When the final batch of prints was in the wash, I would cut up my films into strips, sleeve them for filing, and label each roll with the date and the title “Classifieds – Cars”.

By this time, the final batch of prints would have washed sufficiently and then all the prints were put through an automatic dryer, coming out dry in a matter of seconds. With the prints all dry, they were quickly sorted into number order, labelled on the back for each car yard and taken around to the editor’s desk.

This was never going to be a long-term career, but as already mentioned it was a great learning experience. After I had been at Leader for about six months, a position of Darkroom Technician became available at the Herald & Weekly Times in Melbourne. My interview and darkroom test went very well, and I was offered the job on the spot. Printing all those car photos really paid off.

I spent the next 18 months working in the HWT darkroom, which was another incredible experience. The main darkroom was entered via a short light-trap maze, with no door. Inside were eight work stations around the walls, with a mix of Omega D2 enlargers with Ilford Multigrade heads and Leica Focomat 35mm enlargers. The Omegas were capable of printing up to 4 x 5 but set up at this time purely for 35mm film. Each Omega enlarger also had a drop-board for big enlargements. The Leica enlargers had only recently replaced a number of Durst M605 enlargers, and the autofocus really sped up production.

In the centre of the room stood two Kodak print processing machines, which took the exposed print from dry to dry in under a minute and were large enough to process 20 x 24 prints. This was bliss compared with Leader, as there was no more need for working up to the elbows in chemistry – although as darkroom tech one of my responsibilities, and that of photography cadets, was mixing the chemicals for the machines. These also sped up the whole printing process dramatically, which was necessary in the rush of the daily newspaper environment.

The second darkroom was about half the size of the main darkroom, joining it via a light-tight sliding door. There was another Omega D2 Multigrade enlarger and three Focomats. The D2 was set up mainly for 4×5 negatives, where we printed old negatives, copy negatives produced on a 4×5 copy camera in the nearby copy room, and anything that was a bit out of the ordinary. This darkroom was also where prints were made for Photo Sales, which was a profitable sideline for the paper in the day.

I used to enjoy doing the Photo Sales prints, usually for one full day per week, because it allowed more time to really print the photos to their best, rather than just a quick print suitable for the paper.

At this time, in the late 1980s, newspapers were still mostly black-and-white with the change to colour only just beginning. It was still the heyday of the press photographer, long before the days of social media and instant news reporting from anyone with a mobile phone. When I started there the Herald and Sun newspapers were still separate, not combining for another year, and there were around 40 photographers on staff, working shifts that covered the full 24 hours.

With 40 photographers coming and going, and six full-time darkroom techs, this was a bustling work environment, particularly approaching the twice-daily deadlines, that was often noisy but always friendly. I always found the photographers happy to discuss their work and learned a lot about how to shoot for newspapers.

But the darkrooms were also the scene of many a prank (before the days where everyone gets offended by everything and OHS took the fun out of work). From the first-year cadet “baptism” in one of the large sinks outside the darkroom, to people hiding under the enlarger benches to scare the unwitting, and newbies being sent down to the stores for focusing solution or long-waits to balance the enlargers.

The second darkroom had another entrance, through a revolving door – the scene of many a prank itself. Many people found themselves locked in what became a very loud bass drum. Outside this door were two film processing rooms, each with a set of deep tanks, where films could be processed by hand. This only happened when special treatment was required, like pushing or pulling a film, or doing clip tests. The 4×5 copy negs were also processed in the deep tanks, as well as any medium or large format film that came in from time to time.

The tanks were made of stainless steel and were deep enough to accommodate a 36-exposure roll of 35mm film, doubled over with a weighted roller in the centre. Agitation was via continuous circulation of the chemistry, and regular manual replenishment. The tanks also had stainless steel lids that prevented the developer from oxidising too quickly and could be fitted if the lights needed to be turned on for any reason.

Down a short passage, along the outside of the main darkroom wall, was the main film processing room, which consisted of a small light-tight room with the front of the automated roller-transport film processing machine in it. The bulk of the machine was outside this room near the main darkroom entrance. No plastic leaders were used in the machine. Instead, the leading end of the film would be cut straight and then heat-crimped via a slot in the wall, to enable the processing machine to grab onto the film. If the crimping was not deep enough, the film loaded crookedly or any other number of problems occurred, the film could get stuck in the machine, which could be a disaster. Thankfully this rarely happened.

Colour was becoming more and more common in the papers at this time. The Herald Sun had formed with the merger of the two daily papers, and the number of photographers had been slashed by about 30%. At that time, all colour work for the papers was being shot on slide film and outsourced for processing and pre-press scanning.

In December 1991 I was fortunate to be offered the role as a photographer on the Weekly Times newspaper. About 18 months later the entire business moved from its long-established offices in Flinders St to new offices across the Yarra River at Southbank. The decision was made that we would switch entirely to shooting colour negative film, which would be processed in mini-labs then scanned directly to computers. This was cutting edge technology of the day.

But this meant there would be no darkroom at Southbank, and all the darkroom techs were retrained as scanning techs. The fabulous old HWT darkroom would be closed and all equipment disposed of, with the enlargers going to scrap. I was lucky enough to be given one of the Omega enlargers. Had I known that nearly 30 years later I would be building my own public-access darkroom, I would have grabbed everything.

At the time, I had my own darkroom in the back shed of my home in Melton, in Melbourne’s outer-west. Although very compact, at about 2m x 3.5m, it was large enough for a bench for two enlargers, a light box built into an adjoining bench at right angles, a separate wet area large enough to print 12”x16” prints, and an old upright electric clothes drying cabinet against the fourth wall, next to the door, for drying films and prints. On the wall above the sink I had an electric water heater. There was an inline filter for water coming into the darkroom, plenty of shelving beneath the sink for my trays and chems, and cupboards under the lightbox bench. All in all, a very efficient little space.

I only had one enlarger initially, but I allowed the space for a second one, just in case. My first was an LPL7700 colour, for up to 6x7cm negatives, that I bought new while a student at RMIT and still working in camera shops (so I got it at dealer cost).

The addition of the ex-HWT Omega enlarger meant I was able to print 4×5 negs that I shot with my Toyo 45A field camera, and with my various pinhole cameras that I made from time to time.

The problem was my darkroom had a very low ceiling and the Omega enlarger simply didn’t fit. I overcame this by cutting a hole in the ceiling and building a box that the column and head of the enlarger could go up into. I also built a drop-board for that enlarger.

This darkroom served me well for ten years, but in 1999 I moved to Geelong where I didn’t have space for a darkroom. I was determined that at some point I would have a new one, so packed up my two enlargers and all my darkroom equipment into boxes and stored them in the garage.

I’d left the Weekly Times in 1996 to pursue a career as a freelance photojournalist, specialising in classic cars, motorsport and events photography and reportage. Shooting eventually for ten motoring magazines in Australia, the UK and USA, my work was all on colour slide film, until 2003 when I switched to digital. So, for about 20 years I was without a darkroom and although I had no need for one with my professional work, I always longed for those enjoyable days in the darkroom, where time just seems to slip by.

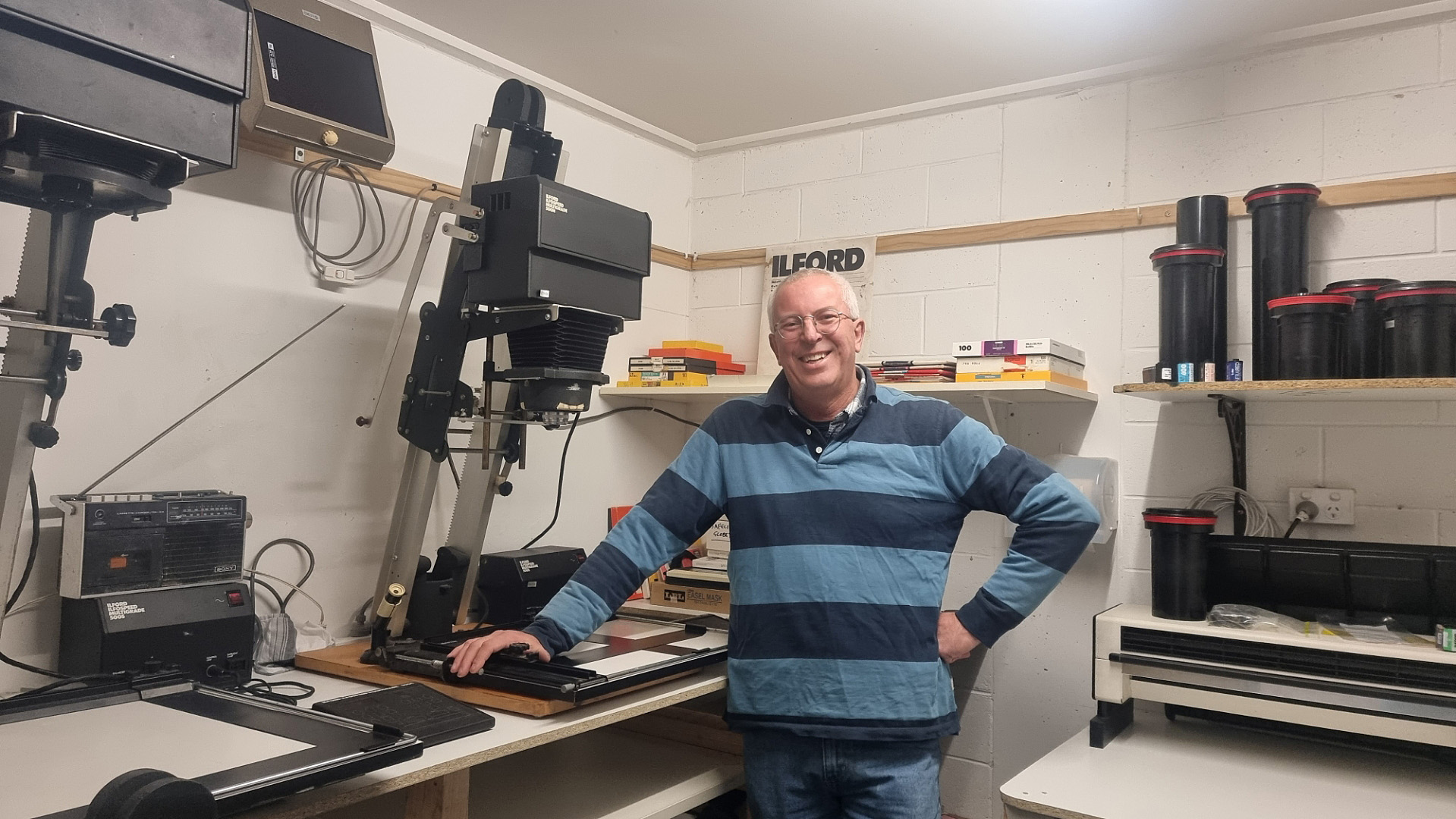

Main photograph above: Craig Watson in The Hue & Cry Collective darkroom.

In part two Craig talks about setting up darkrooms at Focal Point and The Hue & Cry Collective in Geelong.

Previous Post: Exhibition: Bone Country – David Stephenson

Wow really enjoyed your site. I set up a darkroom in the garden shed aged 16 I obtained a position on a Press Photography course at Journalism college I. 1979. I worked as a trainee photographer on a weekly for 3 yrs 3 photographers. Durst enlargers. Then a daily morning and evening paper.. Leitz Focomat enlargers 15 photographers .Had a 35 yr career…..B & W. Colour neg and digital.. Happy days.

Andrew Davies. United Kingdom